Accessible disability history - sharing the past

By Rachael Stamper

In my role as heritage project manager at Queen Elizabeth’s Foundation for Disabled People, a disability charity based in Surrey, UK, I have been exploring how to make disability history more accessible to the general public and for disabled people themselves.

Firstly I would like to talk about a conference I attended at the London Metropolitan Archives in November 2015 titled ‘Disability and Impairment – A Technological Fix?’ The aim of the conference was to share what disability organisations and researchers were doing or with disability history. The conference married together two groups of people, academics and non-academics, and both groups were represented in twelve twenty minute presentations, followed by Q&A sessions.

Academics were present from Lancaster University, The Open University, Langdon Down Museum of Learning Disability, the Wellcome Trust, The National Archives, Yale University, and The University of Exeter. They presented a wide range of topics such as the impact of 20th century computers on people with disabilities, the blind and dead in Victorian Britain 1851 – 1901, and mobility and impairment in the eighteenth century.

Although I have a degree, it is nothing to do with history or disability. Therefore I would like to focus on the presentations given by other groups, as well as talking about my own disability heritage project.

For example Richard Reiser, who is the UK Disability History Month Coordinator, presented a fascinating piece on ‘Examining Representation of Disabled People. Are we Making Progress in Moving Image Media?’ As a wheelchair user himself, he picked out examples of good and bad practice of people without disabilities playing disabled people, such as French comedy-drama The Intouchables or American TV show Glee who both use an able-bodied actor to play a wheelchair user. He argued when people with disabilities are shown on television and film, their disability is always a topic of focus, see American Horror Story: Freak Show, where actors with disabilities played characters who performed in freak shows. Instead he said that agencies should be casting actors with disabilities for characters with disabilities, such as Walter White Junior in Breaking Bad, played by RJ Mitte who has Cerebral Palsy. I think the reason I found this so interesting was that he referenced pop culture from over the last fifty years in a very accessible way, getting the listener to reflect on representation is a way which was easy to understand. It is still an important part of recent disability history, even if it wasn’t researched or presented in a strictly academic way.

Disability charities present were Scope, Leonard Cheshire Disability, and Mencap. You can read about their disability history projects using the links below.

The campaigns officer from Scope talked about their work on marking the twentieth anniversary of the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act.

The Heritage Project Manager from Leonard Cheshire spoke about their £242,250 heritage lottery funded project ‘Rewind’ which seeks to use their archives to raise awareness about the history of disabled people.

A mix of staff including staff members with learning disabilities from Mencap spoke about their £292,900 heritage lottery funded project ‘Hidden Now Heard’ which showcases the hidden heritage of people with a learning disability in Wales.

I am currently managing a £81,400 heritage project at disability charity Queen Elizabeth’s Foundation for Disabled People (QEF). We applied for the funding because it is QEF’s 80th anniversary this year, and we had a huge archive of material sitting in an inaccessible attic, most of which had not been looked at in around fifty years. We had some help in our application; Mike Mantin, a disability history academic from Swansea University, came to do a scoping report of our archive in September 2014. His conclusion was that ‘there is a lot of potentially very interesting material in this archive that paints and extensive picture of the Foundation from a number of viewpoints. The material is very institutional, but read carefully and perhaps paired with oral history this will still be a great resource. There is definitely enough here for a good grant outline proposal.’

As we are a charity, we have excellent trust fundraisers who are accustomed to applying for grants from a range of organisations and funders. Our application was accepted as I was hired to manage the project along with a project consultant with a background in museum work and teaching. You can read all about the types of projects the Heritage Lottery Fund here.

Unlike Leonard Cheshire or Mencap’s project, since our project is under £100,000 we only had to do one round of funding. For my project we get 50% of the budget upfront, 40% after we have submitted a progress report when we have spent most of the first allocation of money, and 10% when we have finished the project and send a final completion report. You have to submit a budget when applying for a project and any changes, such as moving money from one budget line to another, must be agreed with the Heritage Lottery Fund before proceeding. This can be problematic as projects are planned months before they actually start, during which agreed costs and purposes may naturally change.

For example our project did not account for any long-term care and access to our physical archive. By working with a local record office, The Surrey History Centre, we have moved around our budget so that they help achieve some of the key outputs of the project, as well as looking after the archive. To get permission for this we had to submit a request for change to the HLF along with a signed partnership agreement between QEF and the Surrey History Centre. Our collaboration has meant that our archive will be listed by professionals and will be open to all members of the public interested in disability history. I helped to create a number of webpages on Exploring Surrey’s Past which include newly digitised photographs and newly recorded oral histories, further opening up disability history to a wider audience. They also help us to achieve a few more of our agreed outputs which I will talk about below.

Project outputs and how I’m achieving them:

I was prompted to write this after seeing Sebastian Barsch’s post ‘How exclusive is disability history? How inclusive it may be?’ He said that: ‘Perhaps our main task nowadays does not anymore consist in writing disability histories and thus changing an academic attitude towards disability, but make use of the stories that exist and come up with new ones in order to start up discussions and cooperation between academics, artists, persons with disabilities themselves and so on.’ From my work recording oral histories from past beneficiaries, I would completely agree with this. Disability history has naturally been grounded in institutions, using the medical model of disability. Disability historians should be seeking out sources from disabled people themselves, to coin the disability campaigning phrase ‘nothing about us without us’.

I hope I’ve provided a new insight about making disability history inclusive. We are not a campaigning organisation so are not politically driven as a comment from the last blog post suggests, and through our non-academic work we have interested more people and created more primary sources for research than we could have hoped for.

If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to contact me at heritage@qef.org.uk.

In my role as heritage project manager at Queen Elizabeth’s Foundation for Disabled People, a disability charity based in Surrey, UK, I have been exploring how to make disability history more accessible to the general public and for disabled people themselves.

Firstly I would like to talk about a conference I attended at the London Metropolitan Archives in November 2015 titled ‘Disability and Impairment – A Technological Fix?’ The aim of the conference was to share what disability organisations and researchers were doing or with disability history. The conference married together two groups of people, academics and non-academics, and both groups were represented in twelve twenty minute presentations, followed by Q&A sessions.

Academics were present from Lancaster University, The Open University, Langdon Down Museum of Learning Disability, the Wellcome Trust, The National Archives, Yale University, and The University of Exeter. They presented a wide range of topics such as the impact of 20th century computers on people with disabilities, the blind and dead in Victorian Britain 1851 – 1901, and mobility and impairment in the eighteenth century.

Although I have a degree, it is nothing to do with history or disability. Therefore I would like to focus on the presentations given by other groups, as well as talking about my own disability heritage project.

For example Richard Reiser, who is the UK Disability History Month Coordinator, presented a fascinating piece on ‘Examining Representation of Disabled People. Are we Making Progress in Moving Image Media?’ As a wheelchair user himself, he picked out examples of good and bad practice of people without disabilities playing disabled people, such as French comedy-drama The Intouchables or American TV show Glee who both use an able-bodied actor to play a wheelchair user. He argued when people with disabilities are shown on television and film, their disability is always a topic of focus, see American Horror Story: Freak Show, where actors with disabilities played characters who performed in freak shows. Instead he said that agencies should be casting actors with disabilities for characters with disabilities, such as Walter White Junior in Breaking Bad, played by RJ Mitte who has Cerebral Palsy. I think the reason I found this so interesting was that he referenced pop culture from over the last fifty years in a very accessible way, getting the listener to reflect on representation is a way which was easy to understand. It is still an important part of recent disability history, even if it wasn’t researched or presented in a strictly academic way.

Disability charities present were Scope, Leonard Cheshire Disability, and Mencap. You can read about their disability history projects using the links below.

The campaigns officer from Scope talked about their work on marking the twentieth anniversary of the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act.

The Heritage Project Manager from Leonard Cheshire spoke about their £242,250 heritage lottery funded project ‘Rewind’ which seeks to use their archives to raise awareness about the history of disabled people.

A mix of staff including staff members with learning disabilities from Mencap spoke about their £292,900 heritage lottery funded project ‘Hidden Now Heard’ which showcases the hidden heritage of people with a learning disability in Wales.

|

| Logo of the National Lottery |

I am currently managing a £81,400 heritage project at disability charity Queen Elizabeth’s Foundation for Disabled People (QEF). We applied for the funding because it is QEF’s 80th anniversary this year, and we had a huge archive of material sitting in an inaccessible attic, most of which had not been looked at in around fifty years. We had some help in our application; Mike Mantin, a disability history academic from Swansea University, came to do a scoping report of our archive in September 2014. His conclusion was that ‘there is a lot of potentially very interesting material in this archive that paints and extensive picture of the Foundation from a number of viewpoints. The material is very institutional, but read carefully and perhaps paired with oral history this will still be a great resource. There is definitely enough here for a good grant outline proposal.’

As we are a charity, we have excellent trust fundraisers who are accustomed to applying for grants from a range of organisations and funders. Our application was accepted as I was hired to manage the project along with a project consultant with a background in museum work and teaching. You can read all about the types of projects the Heritage Lottery Fund here.

Unlike Leonard Cheshire or Mencap’s project, since our project is under £100,000 we only had to do one round of funding. For my project we get 50% of the budget upfront, 40% after we have submitted a progress report when we have spent most of the first allocation of money, and 10% when we have finished the project and send a final completion report. You have to submit a budget when applying for a project and any changes, such as moving money from one budget line to another, must be agreed with the Heritage Lottery Fund before proceeding. This can be problematic as projects are planned months before they actually start, during which agreed costs and purposes may naturally change.

For example our project did not account for any long-term care and access to our physical archive. By working with a local record office, The Surrey History Centre, we have moved around our budget so that they help achieve some of the key outputs of the project, as well as looking after the archive. To get permission for this we had to submit a request for change to the HLF along with a signed partnership agreement between QEF and the Surrey History Centre. Our collaboration has meant that our archive will be listed by professionals and will be open to all members of the public interested in disability history. I helped to create a number of webpages on Exploring Surrey’s Past which include newly digitised photographs and newly recorded oral histories, further opening up disability history to a wider audience. They also help us to achieve a few more of our agreed outputs which I will talk about below.

Project outputs and how I’m achieving them:

- Digitise 1000 photographs and share these online

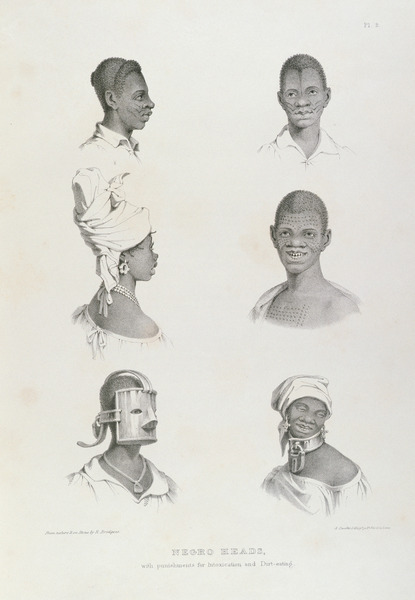

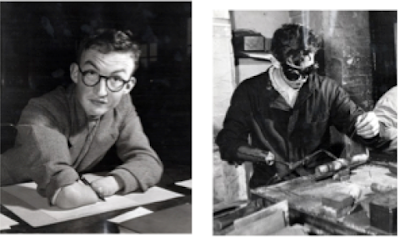

Examples of digitised photographs

I have uploaded all photographs to Flickr, using a team of volunteers to add information written on the back of every photograph. You can view these here. By using Flickr I was able to sort the photographs into decades, service, and theme. Along with tagging photographs for information, this has allowed our photo archive to be easily accessible to the general public. With thanks to a BBC article about the archive we have over 90,000 views.

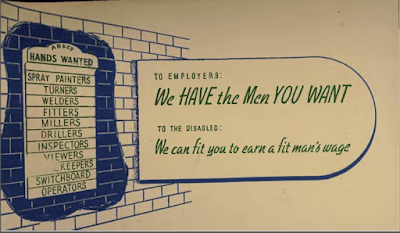

- Digitise 1000 documents and share these online

We have digitised all of our annual reports from 1935 onwards as well as a range of old leaflets and hope to display these on our website soon.

Example of a digitised leaflet - Digitise film reels and VHS tapes and share these online

For this I created a YouTube heritage playlist using our archive material.

YouTube is the most popular free video hosting service which means that more people may be able to find and watch our videos. By using websites like Flickr and YouTube to host an archive immediately opens it up to non-academics who may be put off visiting reading rooms or record offices, or may not even know such places exist. This has also allowed me to easily share videos and photographs with our staff and supporters.

- Create a database of digitised materials

We are working with the Surrey History Centre to achieve this, as they have taken both our physical and digital archive.

- Design and create a travelling exhibition to tour to 10 local towns

We designed our travelling exhibition for a wide audience, focussing on large images and keeping text to a minimum. We have visited shopping centres, libraries, museums, and public record offices and the design of the exhibition reflected this. We have had a good response from members of the public and we encourage them to give us feedback using feedback postcards which are ‘posted’ directly back into the stand.

Our travelling exhibition at the Honeywood Museum, Carshalton, and an example of feedback postcards received. - Work with a theatre group of disabled actors to create a performance about disability history to take to 15 local primary schools

We have been working with the Freewheelers’ Theatre Company who are a professionally led group of disabled actors to achieve this. The Freewheelers wrote and performed the show and I advertised and took bookings for the production. The show is called ‘The Big Laboratory Bang’ and is about two scientists and their trusty robot who have to come up with a new piece of assistive technology to save their laboratory. By looking through the QEF archive for ideas, they create a new wheelchair which wins the prize and saves the day.

A performance taking place at one of the fifteen schools.

The show began touring in late September, delivering performances, Q&A sessions and interactive workshops for over 1,100 children. The Q&A session with the disabled actors allowed children to explore the topic of disability in a safe environment, with questions to the actors varying from ‘what sports do you play?’ to ‘what is it like to be in a wheelchair?’

Feedback from the schools included:- ‘Having the Freewheelers in the school has been good for the whole community’

- ‘This was a unique and incredibly powerful experience for our children’

- ‘It was a great way for the children to develop a greater understanding and empathy for disabled people'

Poster to advertise a public viewing of the show‘The production was lovely to watch, funny, and created in a way where pupils could ask questions and observe in a relaxed environment’ - Research and record oral histories from past QEF beneficiaries

I recorded several oral histories from past beneficiaries and I plan to upload these to YouTube along with a picture slideshow to encourage people to listen to them.

- Design and create a static exhibition to be held in London for one week

Our exhibition it titled Crippled, Handicapped, Disabled: Living Beyond Labels and is at gallery@oxo, Oxo Tower, London from 20-24 April 2016. We are using our newly digitised photographs, research, oral histories, digitised films and a range of objects to explore how attitudes towards disability have changed over the last eighty years. You can read more about the exhibition here.

The gallery is on London’s South Bank so we’re hoping to have over a thousand visitors to the exhibition across the five days we are open to the public.

|

| Project coverage from the BBC. |

I hope I’ve provided a new insight about making disability history inclusive. We are not a campaigning organisation so are not politically driven as a comment from the last blog post suggests, and through our non-academic work we have interested more people and created more primary sources for research than we could have hoped for.

If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to contact me at heritage@qef.org.uk.

Recommended Citation

Rachael Stamper (2016): Accessible disability history - sharing the past. In: Public Disability History 1 (2016) 4.

Rachael Stamper (2016): Accessible disability history - sharing the past. In: Public Disability History 1 (2016) 4.