By Michaela Caspar

Translated by Ylva SöderfeldtIf we look for the history of the Deaf in archives and libraries, we tend to find mostly hearing people. Hearing doctors, teachers, clergy, philosophers, linguists, or politicians and their perspective on deafness and signed languages. The hearing have documented the history of the Deaf. But what do the Deaf have to say?

|

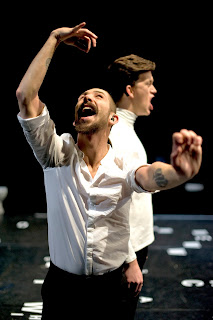

| Five actors on stage. Photo: Lisa Wischmann |

In order to connect current controversies on the cochlear implant (CI) with their historical background, the audience is invited to join the eight Deaf and four hearing actors on a journey through the history of the Deaf. This is the story of a largely unknown, but vital community with its own language and culture, but it is also a history of persecution and oppression.

An inclusive process

|

| Heinicke's oral method. Photo: Lisa Wischmann |

In order not to reproduce paternalistic structures in the artistic process, we agreed on three rules:

- We will not start with a written manuscript.

- We will avoid material written by hearing authors when we do research.

- The development of the piece is a group process.

Throughout the piece, we connected improvisations on current, personal experience to previous controversies within the Deaf community. The opposition to CIs within parts of the Deaf community resembles the resistance to oral education of previous generations, but just like many Deaf in the 19th century welcomed oral education, there are also contemporary Deaf people in favor of CI. This is reflected in the closing statements by Eyk Kauly and Wille Felix Zantes:

"Who gives you, hearing people, the right to interfere with Deaf bodies?... Deafness is not just a hearing impairment. Deafness shapes our identity!"

-Eyk Kauly

"Should this four month old baby get a CI? Yes! It’s the future! Through technical progress we’re able to optimize the entire human race. We should take this opportunity… Let’s see the big picture here, beyond language, let’s create a real superhuman!"

- Wille Felix Zantes

Putting a script together using group exercises and improvisation

|

| Total view of the stage. Photo: Jan-Peter E.R. Sonntag |

Interviews with survivors

Parallel to or work with improvisations we contacted a group of Deaf seniors. After we’d spent some time together, eight of them agreed to be interviewed. We prepared for the interviews by studying the literature of Deaf communities under the Nazis and in the 1950s-1970s. The interviews were filmed and excerpts integrated in the piece, relating to the topics oral education and National Socialism.The Deaf Time Machine contains many of the personal views and experiences of the actors. However, one of the most personal and intense experiences we had during repetitions was the encounter between generations. We were honored that the seniors told us about their lives, especially since what they had been through was often very painful. Two of them passed away last year, but we take comfort in that they live on in the play and keep bearing testimony to us all about the history of the Deaf.

Interview with Ms Schubert, Berlin 2014:

(Please download translated transcript here)

Direct Link to video.

Making of-Video:

Direct Link to video.

Pictures copyright by Possible World e. V.

Videos: Jens Kupsch

Recommended Citation

Michaela Caspar (2016): "When your past is omitted in the history books, it’s invisible“: The Deaf Time Machine. In: Public Disability History 1 (2016) 1.

1 1774-1838, French physician and teacher oft he Deaf, (in)famous for his oralist attitude and attempts to cure deafness with experimental methods.↩

2 Translator’s note: this is an English translation of a German transcript of DGS.↩