By Valerie Doulton

Martineau’s Childhood and the Beginnings of Deafness

“Now and then, someone made light of it. Now and then, someone told her that she mismanaged it, and gave advice which, being inapplicable, grated upon her morbid feelings; but no one inquired what she felt, or appeared to suppose that she did feel. Many were anxious to show kindness and tried to supply some of her privations; but it was too late. She was shut up, and her manner appeared hard and ungracious while her heart was dissolving with emotions.” (Martineau 1861, 118)

Her writing describes that within her immediate family circle, Martineau had at aged 16, become alone and excluded. It also appears she received little sympathy, from either her parents or siblings. It was perhaps this realisation that she could not necessarily rely on other people which was instrumental in her decision to make her own life. In her later ‘Autobiography’ she writes:

“I must take my case into my own hands; and with me, dependent as I was upon the opinion of others, this was redemption from possible destruction. Instead of drifting helplessly as hitherto, I gathered myself up for a gallant breasting of my destiny; and in time I reached the rocks where I could take a firm stand. I felt that here was an enterprise; and the spirit of enterprise was roused in me!” (Martineau 1983, 76)

|

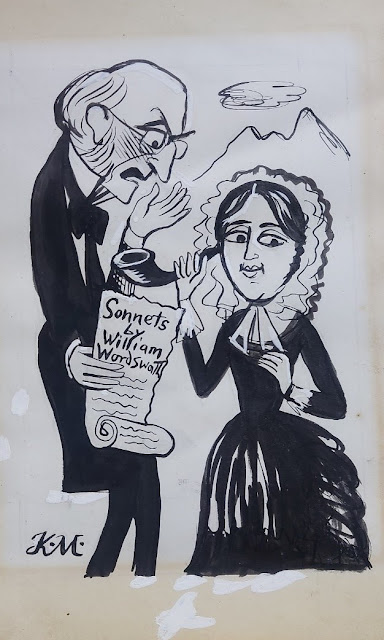

| Figure 1 - Harriet Martineau and Her Ear-Trumpet |

What we know of Martineau’s independence of mind, as shown in so much of her writing, was formed directly from her experience of coping in her own independent manner with the deafness that emerged in her childhood. Alongside, this she also developed a great self-discipline and at the age of twenty-eight, when she first began using an ear trumpet, she was able to greatly reduce the barrier which her hearing loss had created between herself and other people. This use of the ear trumpet was a visible sign of what some contemporaries would highlight as a disability. Erving Goffman defines it as a ‘stigma’. These critics portray Harriet as stigmatized by a disability and also marginalized by her gender. They exaggerate her appearance with the ear trumpet as grotesque and abnormal.

The 19th century politicians and commentators who did not want to accept Martineau as a significant writer and social theorist tried to socially disqualify her on account of both her deafness and her sex. The M.P. Lord Brougham dismissed her as ‘the little deaf woman from Norwich’.

In her 1834 Letter to the Deaf Harriet encourages the community she is addressing to nevertheless take up the ear trumpet:

“Yet how few of us will use the helps we might have! How seldom is a deaf person to be seen with a trumpet! How should I have been diverted, if I had not been too much vexed at the variety of excuses that I have heard on this head since I have been much in society. The trumpet makes the sound disagreeable; or it is of no use; or it is not wanted in a noise, because we hear better in a noise; nor in quiet, because we hear very fairly in quiet; or we think our friends do not like it; or we ourselves do not care for it, if it does not enable us to hear general conversation; or- a hundred other reasons just as good.

Now dear friends believe me, these are but excuses. I have tried them all in turn, and I know them to be so. The sound soon becomes anything but disagreeable; and the relief to the nerves, arising from the use of a trumpet is indescribable. None but the totally deaf can fail to find some kind of trumpet that will be of use to them, if they choose to look for it properly and given it a fair trial.” (Martineau 1838, 27-28)

Harriet Martineau’s Travels in the United States

Martineau valued her own ear trumpet to the extent that it accompanied her on her travels round America in the 1830s.She did not only travel as a tourist. She engaged actively in very contentious debates about racial segregation and the slave trade, writing passionately against both practices and as an outspoken abolitionist. That many of these extremely fractious engagements were entered into using an ear trumpet summons up a picture of immense courage and strength of character.

Life in the Sickroom

How fiercely and proudly Martineau made for herself a place in society. In doing so she also demonstrated that whole categories of supposedly gendered behaviours are insignificant if not obsolete. In her 1998 book Mesmerized: Powers of Mind in Victorian Britain, Alison Winter argues that Martineau also overcame all the limitations of the sick room. For in addition to learning how to live best with her deafness, she also in later life suffered a long period as an invalid. In Invalidism and Identity in Nineteenth Century Britain, the literary historian Maria H. Frawley argues that Martineau:

"… moves with evident assurance from an account of sights seen ‘through one back window’ to the ‘truths of life’ that such sights reveal to her."

She was confined for about 5 years in a room in Tynemouth, near Newcastle. During this time, looking through her window from her sickbed to the sea view beyond led her to dwell on macrocosmic truths. This she describes in ‘Life in the Sick Room’ published in 1844.

A Wider and Deeper Understanding of Life

Deafness can throw the individual into a profound interior world, which for some is a profound isolation. Martineau’s feelings about deafness were from a first-person perspective, a matter of ‘lived experience’, to which she always referred herself, and drew very individual conclusions. She did not adhere to the rationalist theory of body prevalent in medical authorities in western societies, in which the body is viewed as an ‘object’. In The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability (1997), Susan Wendell argues that this approach drives a wedge between doctors and patients – encouraging doctors to view the latter as no more than the physical manifestation of collections of symptoms. Perhaps even more significantly, it serves to alienate patients from their own experiences. (Wendell 1996, 136)

Martineau had extraordinary interior contact made more profound through deafness, and she came to analyse her body and its function as ‘lived personal experience’. This may have been a reaction to the complaint quoted above, which appeared in her 1828 book Household Education - that no one inquired what she felt, or appeared to suppose that she did feel. Feelings, as opposed to the rational, are often discussed by medical practitioners as ‘purely imaginative’. But Martineau believed that invalidism had equipped her and all fellow sufferers with powers of perspective unknown to the healthy. Harriet Martineau clearly wanted her readers to understand the subjective experience of illness- i.e., what the long-suffering felt and how they experienced life in the sickroom. She authored her book anonymously as ‘an invalid’ at times directing her remarks to a readership of ‘fellow-sufferers’ and ‘unknown comrades in suffering,’ a readership she had addressed earlier in her 1834 ‘Letter to the Deaf’.

A Woman Ahead of Her Time

In this and her views on gender and other issues, Martineau was way ahead of her time. She argued that availability of education, which privileged her own mind, must become the standard for all women. She wrote,

"What we have to think of is the necessity – in all justice, in all honour, in all humanity, in all prudence – that every girl’s faculties should be made the most of, as carefully as boys."

She believed that the cultivation of the female intellect is a necessity. Neither her deafness nor her gender impeded her life’s work. Her critics saw both as her greatest liabilities. But they were the foundation of her courage, intellect, and the fulfilment of her life’s work. In other words, her empowerment. In our own time of long Covid, Harriet Martineau’s experience of long-term illness speaks to us very meaningfully today.

Hail to the steadfast soul,

Which, unflinching and keen,

Wrought to erase from its depth,

Mist and illusion and fear!

Hail to the spirit which dared

Trust its own thoughts, before yet

Echoed her back by the crowd!

Hail to the courage which gave

Voice to its creed, ere the creed

Won consecration from time!

- Matthew Arnold, describing Martineau in his poem ‘Haworth Churchyard’ (1855)

This is an edited version of the Live Literature Company’s podcast on the nineteenth century polymath Harriet Martineau (1802-1876). Much of the information in this podcast was first given in a talk entitled Harriet Martineau and her Deafness- Disability or Empowerment? delivered to the 18th Martineau Society Conference in July 2012. The talk referenced Anka Ryall’s study, Medical Body and Lived Experience: The Case of Harriet Martineau (2000), as well as to Susan Bohrer’s paper, Harriet Martineau, Gender Disability, and Liability (2010), and to Vera Wheatley’s biography, The Life and Work of Harriet Martineau (1957). This is considered worldwide to be the first important biography of Martineau, and it is held in great esteem by members of the Martineau Society. In addition, Valerie Doulton, the author of this post, is Wheatley’s granddaughter, and Wheatley’s biography inspired her to join the Martineau Society. Doulton is also the founder and Artistic Director of The Live Literature Company (https://www.theliveliteraturecompany.co.uk) The Company was founded in 2002 with the aim of creating high-quality drama that is accessible to the widest possible audience.

_____________________

References:

Harriet Martineau, Household Education (London: Smith and Elder, 1861 [first published 1828]), p.118.

Harriet Martineau, Autobiography (vol.1) with a new Introduction by Gaby Weiner, (London: Virago, 1983). p.76.

Harriet Martineau, A Letter to the Deaf (London: C. Knight and Co., 22 Ludgate-Street, 1838), pp.27-28.

Susan Wendell, The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability (New York/London: Routledge, 1996), p.136.

Recommended citation

Doulton, Valerie (2023): Her manner appeard hard and ungracious, while her heart was dissolving with emotions´: Harriet Martineau and Her Deafness. In: Public Disabilitiy History 8 (2023) 4.