Historians of slavery must often contend with how the power imbalances of the slave system continue to shape the archival record, and, more importantly, influence the types of stories that get told. I certainly found this to be the case when writing my first book, Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840 (University of North Carolina Press 2017). I felt overwhelmed as I weighed the written correspondence, published medical treatises, military records, and plantation records, medical lectures etc. by white physicians, military officers, colonial elites, and slave owners, against the dearth of written sources left behind by enslaved and free black people. Thus, it was a great challenge to construct a narrative using sources whose faithfulness in accounting for black people’s experiences in sickness and health were tenuous to say the least.

Given the realities of the archives related to slavery, my approach to research became informed by working with the asymmetries in my evidentiary sources rather than against them. Part of what I hoped to achieve with my book then, was to not only show how blackness formed a corpus of knowledge that white physicians used to cultivate their medical authority and professional expertise, but also to show how enslaved people shaped this often contradictory and protean process. I tried to amplify the experiences of enslaved people as recipients of white medical treatment and as objects of white medical gazes, rather than “speak” for them. I reminded myself as I wrote the book that the doctor-(subjugated) patient relationship was a two-way street—one in which the balance of power was in flux. Physicians had to read patients’ bodies for clues and inquire about symptoms; slaves could dissemble, lie, or even be forthcoming when they described their symptoms. Physicians could also ignore slaves’ symptoms if they did not fit their expectations of how a slave’s body should respond in times of sickness, and, in some cases, physicians simply failed to understand the meaning of their patients’ symptoms. Bearing all of this in mind, I thought about why white physicians presented the information about black people’s bodies in the way that they did. What was at stake for these physicians? And how did a physicians’ pronouncement that enslaved person was diseased help create a new identity for that slave in the plantation economy and community?

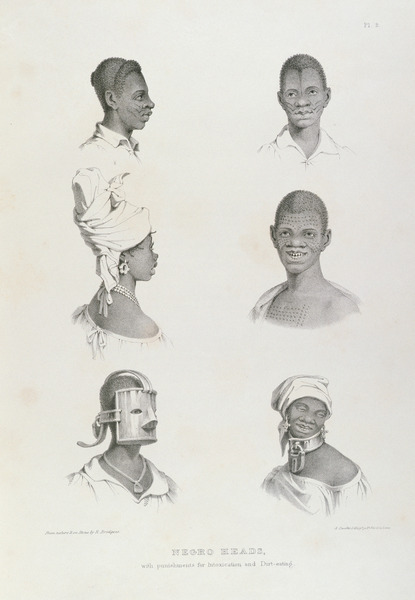

|

| Heads circa 1836 Richard Bridgens |

I applied this line of questioning in my book’s chapters on Cachexia Africana—a little known slave disease that only affected black people. It was typically attended by dirt eating and a gradual wasting away of the body. Cachexia Africana was a creation of the collective white imagination; it was a pathology only found in black people, hence the name Cachexia Africana or “African wasting.” Doctors no longer use the label nowadays, but it appeared in medical texts during the era of slavery. Dirt eating, however, could apply to anyone of any race, and has been known as pica or geophagy. Generally speaking, Cachexia Africana often appears as a footnote or a brief reference in many scholarly works on slave health. Some scholars have pointed out that Cachexia Africana was just one of many socially constructed slave diseases. Others have used this disease as means to highlight the nutritional deficiencies that plagued enslaved black people’s bodies.

In Medicalizing Blackness, I used Cachexia Africana to illuminate how enslaved people challenged white physicians’ authority. Moreover, I also used the disease to show how white conceptions of what was normal versus pathological in black people’s bodies was deeply contingent on context and largely socially constructed. Throughout this process I used the very discourses that white physicians had generated about the alleged physiological deficiencies in black people—the very sources that seemed to replicate the power of slavery in the archive. I took the approach of scrutinizing what it was that white physicians said (or didn’t say) about Cachexia Africana and its victims in medical texts. For example, many physicians complained about treating slaves who fell victim to Cachexia Africana more so than other common diseases they encountered. Most physicians who wrote about Cachexia Africana did so in treatises or dissertations dedicated to “negro diseases” or plantation medicine, and they lost no time boasting of their medical skill (many of the physicians who wrote about the prevalence of this disease on Jamaican plantations studied at renowned medical schools such as the University of Edinburgh). When these physicians failed to treat Cachexia Africana, why did they spend so much time complaining about it—thereby drawing attention to their professional shortcomings? What did their failures say about the limitations of white medical knowledge and education in the disease environments of the Caribbean? For physicians that blamed enslaved spiritual healers for bringing on the disease or exacerbating it, was this a way for them to excuse their inabilities to affect cures? (Physicians did not mince words when it came to complaining about enslaved practitioners!) Enslaved practitioners likely enjoyed more trust and respect within the enslaved communities in which they practiced than white physicians. Bearing this in mind might explain why white physicians felt that they were being undermined as they tried to treat Cachexia Africana. Indeed, European physicians who practiced in slave societies acknowledged that enslaved healers simply had more effective treatments than what Western medicine could offer—a topic expertly examined by Londa Schiebinger’s Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World. We can perhaps surmise then, that white physicians who attempted to treat Cachexia Africana were irritated by competition from enslaved healers and hemmed in by ineffective treatments.

Finally, textual descriptions of the symptoms of Cachexia Africana made legible the ways white physicians imposed concepts of normalcy or pathology on enslaved people’s bodies—a practice that might perhaps be familiar to scholars interested in disability studies. Cachexia Africana curtailed slaves’ ability to labor, and slaves that were unable to labor were viewed as suffering from some kind of pathology (hardly ever overwork). In a sense, Cachexia Africana, served the purpose of reinforcing narratives that equated a slave’s ability to labor with normalcy. Here I would add, that due to the extreme deprivation and exposure to unsanitary conditions that slaves endured on the Middle Passage, and the plantation, the bodily fitness which slave owners and overseers desired in slaves appears to be more aspirational than real. Similarly, we might consider what other definitions of fitness that have appeared across time worked as social constructs to satisfy idealized rather than real ideas about health. Re-examining how concepts of pathological versus normal traits emerged through writings about diseases generate new questions to ask of our archive and historical actors regardless of area of interest. In sum, recovering the experiences of marginalized groups often involves interrogating what they did or did not do in the face of oppressive medical authorities; noticing how and why their very bodies could create such contempt for those who wrote about them.

Rana Hogarth is assistant professor of history at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Recommended Citation:

Rana Hogarth (2018): Eating Dirt, Treating Slaves. In: Public Disability History 3 (2018) 10.