My previous post looked at the ways in which organisations and individuals within the British disability movement have used references to, and symbols connected with, the Nazi persecution of disabled people. I argued that early references were intended both to encourage a sense of common identity amongst disabled people, and to demonstrate that they were an oppressed minority. This latter interpretation was radically different from the traditional view of disabled people as suffering exclusively from their impairments. In this post, I am going to discuss Tanvir Bush’s forthcoming novel CULL, and Liz Crow’s 2008 documentary, exhibition, and art installation, Resistance. In their different ways, both of these engage creatively with the Nazi persecution of disabled people and ask what relevance this has today.

Although Bush’s novel Cull is not due to be published until January 2019, she has written an as-yet unpublished article in which she explains the novel’s themes and how the Nazi analogy is used in it. Similarly, Crow’s website contains a number of articles shedding light on various aspects of the creation of Resistance. As Bush explains,

"CULL is a dark, satirical novel that hypothetically asks what could happen if the UK government sanctioned state-sponsored euthanasia as a social cost-cutting exercise?"2

‘Grave and systemic violations of disabled people’s rights’.

Bush explains in an afterword that she was inspired by the publication, in November 2016, of a United Nations report which found that the UK government was responsible for ‘grave and systematic violations of the rights of disabled people in the UK’3. The majority of the violations cited involved the UK government’s cuts to disability benefits and its relentless drive to get disabled people into work and ensure that benefits were not a so-called ‘lifestyle choice’4. The UN reiterated its findings in 2017, and Theresia Degener, the head of the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) stated that the government’s ‘fitness to work’ tests ‘totally neglected the vulnerable situation people with disabilities find themselves in’5.

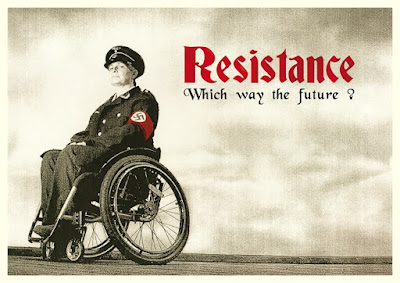

|

| Liz Crow in her wheelchair dressed as a Nazi |

Liz Crow’s Resistance was motivated in part by similar concerns:

"For disabled people, we find ourselves in the midst of a new system of benefits that has been charged with contributing to the deaths of thirty-two disabled people every week, a tabloid press campaign that is portraying disabled people as fraudsters and scroungers … an associated hardening of public attitudes towards disabled people, and a chilling rise in hate crime. Within these events are knife-edge judgments of our place in the world, a step away from whether we even deserve to exist at all."6 |

| Elise makes her bid for freedom © Roaring Girl Productions |

Gallagher had mentioned a woman whom he referred to as ‘EB’, a patient at an institution in Nazi Germany, who was employed there as a cleaner. Gallagher wrote that ‘EB’ made a bid for escape, going around rather than inside the bus which had arrived to take her to her death.7 By the time of her posthumous arrival in Liz Crow’s Resistance, ‘EB’ had morphed into the pivotal character of Elise Blick. As Crow shows, the character’s surname was chosen quite deliberately:

The Importance of Names.

|

| Elise and her broom outside the institution © Roaring Girl Productions |

Crow’s film does – taking its cue from Gallagher’s By Trust Betrayed, it brings the possibility of disabled resistance to a much wider audience, and – crucially – shows disabled people valuing their lives and wanting them to continue. Crow further took the decision to name all the disabled characters in Resistance, while leaving the institution staff anonymous – a further act of reclamation, showing that the people who were killed are more worthy of remembrance, than those who facilitated their murder.

|

| Frontcover of Bush’s novel CULL |

Names are also of importance in Tanvir Bush’s novel CULL. Bush includes various references to the Nazi ‘euthanasia’ programme and to the ideas and persons which helped to facilitate it. Two of her characters – a celebrated physician and his daughter, a rising politician – have the surname Binding. This is a reference to Karl Binding, who, with his colleague Alfred Hoche, wrote Die Freigabe der Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens (The Granting of Permission for the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life), published in Leipzig in 1920. Bush describes this tract as ‘the blueprint for the Aktion T-4 Plan and the staunch defence of many of the doctors.’9 There is also an incidental character called Dr Julian Hallywooden, whose unusual surname came about because it refers to Julius Hallervorden, the German neuroscientist whose glittering research career was not impeded by his having participated in the Nazi ‘euthanasia’ programme. Bush states that her aim in doing this was not to test her reader’s historical knowledge, but that "readers who made the connections might receive a jolt of pleasure, like finding a key clue to a crossword"10.

|

| The grey ‘murder-box’ bus © Roaring Girl Productions |

Bush’s image of finding a key clue in a crossword is apposite, but I wonder if instead of receiving a jolt of pleasure, a reader might be motivated to think more deeply about why Bush had chosen to allude to persons instrumental in the Nazi ‘euthanasia’ programme. The decision was clearly taken to make a point. The same is true of the grey Community Transport ambulance which makes its first appearance at the beginning of the novel, and which Bush writes is "based on the very ones in Germany that had picked up the disabled children and adults for euthanasia … in the 1930s"11.

That Bush’s novel is set in modern-day Britain, but alludes to the Nazi ‘euthanasia’ programme, is particularly striking, showing that there are things for every society – not just Germany – to consider. In fact, both Bush and Crow make this explicit. Bush’s novel shows how policies which make life avoidably harder for disabled people facilitate lack of understanding, foster the growth of stereotypes and hate crime, and allow a cavalier attitude towards the value of disabled lives. The novel also shows that these attitudes would be much harder to sustain without a complicit media, and of functionaries who either actively believe that people from targeted groups are merely representatives of types, or who simply do as they are told without question.12

"A soundtrack of voices, disabled and not, talking about their experiences of discrimination … they speak of practical and emotional cost, but also describe the elation of being included. Audiences glimpse a starting-point for making that inclusion a reality and are shown the possibility of their own role in this."13

The differing approaches of these two works, and the different solutions they offer, makes the idea of seeing them as companion pieces, with each illuminating aspects of the other, attractive. They also demonstrate beyond doubt that the subject of the Nazi persecution of disabled people is one to which is still relevant, and also one to which disabled people are continuing to bring new and important insights.

Emmeline Burdett (emmelineburdett@gmail.com) is an independent researcher.

___________________

[1] I would like to thank Pieter Verstraete for his comments on a previous version of this post.

[2] Tanvir Naomi Bush, unpublished article explaining the genesis of CULL, 1.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Quoted in ibid, 2.

[6] Liz Crow, ‘Resistance: The Art of Change’, www.roaring-girl.com/ wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Resistance-The-Art-of-Change.pdf , 4.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid,14

[9] Bush, 5.

[10] Ibid, 7.

[11] Ibid, 8.

[12] Ibid, 4.

[13] Crow, ‘Resistance: The Art of Change’, www.roaring-girl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Resistance-The-Art-of-Change.pdf.

Recommended Citation:

Emmeline Burdett (2018): Reclaiming Our History? Creative Responses to the Nazi Persecution of Disabled People, Part II. In: Public Disability History 3 (2018) 15.