This article is based on a wider dissertation on ‘The Changing Attitudes Towards Down syndrome in Post War Britain’ written in 2019. It discusses the role of parental advocacy as a force for evolutionary change towards the inclusion of people with Down syndrome in post war Britain. I will therefore be focusing on the movements towards integrated education and the process of de-institutionalisation, as well as commenting on the introduction of the pre-natal test and its effects on the parental community. At the start of the post war era, most children with Down syndrome were transferred to institutions and many were deemed ‘uneducable’. With the help of the parental movement, institutions were improved, community living was becoming a reality and education for people with intellectual disabilities like Down syndrome was more accessible and integrated. Whilst the parental movement helped change attitudes towards Down syndrome, it was not revolutionary and represents a piece within an evolutionary process that continues to this day.

This article includes some specific examples which, whilst they cannot be generalised do provide insight into the types of attitudes prevalent of the time.

The Growth of Parental Advocacy

The introduction of the pre-natal test, in some ways negatively affected attitudes towards Down syndrome, as it revealed an ‘anti-disability sentiment within society’ (Furedi 2016: 77). Parental attitudes towards Down syndrome in the 1970’s and 1980’s however were generally more positive than in the immediate post war decades. The introduction of the amniocentesis test which tested foetuses for conditions like Down syndrome and the legalisation of Abortion in 1967, meant that women who gave birth to babies with Down syndrome had generally chosen to. The increase in the conscious decision by mothers to keep a pre-diagnosed pregnancy was likely a cause for the increase in parental support groups in the 1980s. Support groups such as The National Association of Parents of Backward Children, now known as MENCAP, challenged the stigma attached to having a child with disabilities like Down syndrome. A report from Living with Handicap, a working party set up by the National Children’s Bureau in 1974, suggested that ‘Perhaps the greatest help we had …was to talk to other parents with a child with a handicap like ours’ (Dame Eileen Younghusband committee 1974). Therefore, choice meant those having children with Down syndrome were more likely to advocate for them, strengthening the community.However, due to the fallibility of the test, some foetuses went undetected, thus some mothers gave birth to children with Down syndrome without knowing, or possibly wanting the child. For example, Mary Craig, a mother of a 12-year-old boy with Down syndrome stated, ‘I know all the horror, shame, disgust and fear that you feel initially at having given birth to an imperfect child’. However, she later argued ‘Nicky has given all the family so much’ (Grosvenor 1981). This could therefore suggest that the increase in the support groups and the availability of choice due to pre-natal testing, helped change the minds of those who previously may not have chosen to give birth to a disabled child.

Deinstitutionalization and Community Living

In the early post-war era, children with learning difficulties were often assigned to institutions or hospitals, mostly as a result of professional advice. Anne Crosby, who had a son with Down syndrome in the 1960’s, was unsure where the best place for her child was and so consulted a doctor. The doctor advised her to place him in an institution, heartbreakingly labelling him as ‘the throw away child’ (Sandino 2003). |

| Picture showing Matthew Crosby in the 1960s. Taken from – Charlotte Moore ‘The Throwaway Child’ The guardian (23/05/2009). |

However, during the 1970s and 1980s, an initiative started by parents, which saw integration into the community as a possibility (Russell 1996: 80). As the post-war era progressed, parental charities began introducing projects to promote transition to community care. In 1958, the parent led charity The National Society for Mentally Handicapped Children carried out the Brooklands Experiment. This showed how effectively a child with intellectual disabilities in a home environment could develop compared to an institution and the results were published around the world. Although, some parents openly advocated for their children, some expressed advocacy more subtly, which was difficult to record. Eileen Clark, a mother of a child with learning disabilities, was a strong advocate for community living in the 1980’s. In a podcast for the Hidden Now Heard MENCAP project, she suggested, ‘The parents wouldn’t stand up for themselves’ (Hunt 2016). However, Clark also stated that her influence encouraged some parents to openly stand up against the authorities for the rights of their children. This highlights the power of parents in encouraging others to demand change, particularly in the introduction of community services. It does, however, suggest that by the 1980’s attitudes were not transformed and although many did, some parents still did not forthrightly advocate for their children.

One motivation for campaigns against institutional living and an improvement in services was the institutional scandals of the 1960’s and 1970’s. Maureen Oswin’s The Empty Hours: Weekend Life of Handicapped Children in Institutions published in 1973, exposed the unsuitable environment of institutions. It found that children in hospitals ‘are vulnerable to various forms of deprivation’ such as ‘intellectual deprivation, incompleteness and deep-seated unhappiness’ (Oswin 1973: 150). The Cardiff Ely hospital report, published in 1969, also questioned institutionalisation and inadequate services provided in institutions. The Ely Report found ‘cases of bad management, poor nurses and callousness’ (Wilkinson 1969). One such example was of a boy with Down syndrome who had his nails cut so short, ‘to an extent that must have been painful.’(The committee of Inquiry 1969) This can be used to demonstrate the types of negative attitudes towards Down syndrome in institutions in the 1960’s. As a reaction, The Campaign for the Mentally Handicapped, which was predominantly led by parents, started a movement to improve services. This took the form of a petition of 12,000 signatures, which was sent to the government in 1974. As a result, the care at Ely hospital was radically improved and the scandal caused ‘the momentum to close the long-stay hospitals’ (Wales online 2012). These scandals therefore publicized poor conditions of institutions, encouraging parents and other individuals to demand improvement for care services and ultimately end the institutionalisation of people with intellectual disabilities.

|

| A photograph showing a group of nurses and patients walking outside Ely. ‘outside of Ely Hospital’ The Peoples Collection- copyright Mona Hussey. |

|

| Photograph of a child at Ely Hospital in 1967 by Jurgen Schadeberg. |

Education

In 1945, some children with Down syndrome were not given an education, as those who were ‘severely handicapped’ were considered uneducable under the 1944 Education Act. From 1950-1977, segregation was occurring, with 55,00 children in 1955 in special schools and 135,261 in 1977 (Cole 2012: 33 –34). Whilst this could indicate more children were receiving an education, the exclusion of children from mainstream education only enforced negative attitudes towards disability. Despite this, parental advocates fought for change in the post-war decades, with many parents rejecting the segregation of children into special schools and pushing for educational inclusion. The Plowden report of 1967 helped recognise the need for educational inclusion and highlighted the significance and importance of the parental movement for the desegregation of education in mainstream Britain (Maguire 2006: 73).The Education Act of 1970 entitled all children the right to education, encouraging the introduction of the Warnock Committee of Enquiry, which reviewed special education (Barton 1997: 146). The Warnock report in 1978, recommended that the term ‘special educational needs’ be adopted and normalised disability by suggesting 20% of children had some level of learning disability (Warnock et al. 1978). The report suggested statements of disability should be introduced and local government should be obliged to make provisions based on these. The 1981 Education Act was to implement these recommendations. However, because the report did not make economic recommendations, the Act allocated almost no resources to special education, demonstrating the governments ‘evasiveness about integration’, because of economic cost (Warnock 1996: 55). Despite this, the 1981 Education Act encouraged educational integration to become a reality in the 1980’s (Select Committee on Education and Skills Third Report 2006). As a result, contemporary Brian Stratford argues more professionals were ‘aware of the potential of Down syndrome children’ (Stratford 1985: 149). Integration of disabled children in mainstream schools in the 1980’s caused a change of attitude, as society was becoming more exposed to disabilities and thus feelings of ‘otherness’ were dissolving. Ann Borsay supports this, suggesting educational integration ‘is the most effective way of challenging negative attitudes…. And developing a more tolerant and open society’ (Borsay 2012).

Parents were however often met with resistance by education professionals. For example, MP Clement Freud stated in 1980, that teachers frequently responded with, “We do not take Mongols at this school; the other parents would not like it", when asked to take a child with Down syndrome. Nevertheless, some educational professionals worked to support the parental movement. Teacher and advocate Stanley Segal, for example, was extremely influential in the strive towards integration, after writing his book No Child is Uneducable in 1967. This supported the need for integration and better education for children with disabilities, challenging the assumption that some children with disabilities were uneducable. Segal therefore aided the parental movement and helped reinforce the need for the education acts of the 1970s and 1980s.

Douglas Hunt was a retired headmaster and parent to Nigel who had Down syndrome. In 1967, Douglas encouraged his son Nigel to write his own book, entitled ‘The World of Nigel Hunt; the diaries of a Mongoloid youth’. This book helped reinforce the educational capabilities of people with Down syndrome. The preface of the book includes a note from researcher L.S Primrose, who comments on Nigel’s ability and suggests he will ‘go on learning notwithstanding his extra chromosome’ (Hunt 1967: 10). Whilst the contents of this book are not complex, it does represent a transition from parental advocacy to self- advocacy. Primrose supports this, suggesting the book allowed Hunt to ‘speak on behalf of thousands of similarly effected people’ (ibid.). This book therefore demonstrated the abilities of children with Down syndrome and reinforced the need to provide better education. However, it also represents the transition to self-advocacy, where parents encouraged their children to find and use their own voices.

|

|

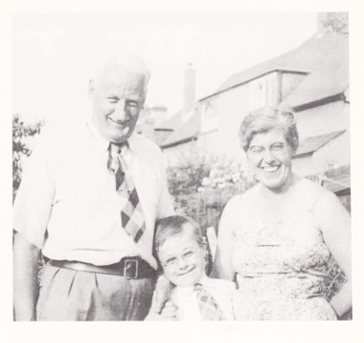

Nigel

with his parents- taken from Nigel Hunt (1967): The World of Nigel Hunt, the

diary of a Mongoloid youth, New York.

|

Conclusions and the birth of self-advocacy

The change in attitudes towards Down syndrome in post war Britain was not revolutionary or linear. The parents that took part in the advocacy movement for educational and community integration, encouraged a progression in attitudes and dispelled the social assumptions of ‘otherness’, by pushing for their children to be in the mainstream. Additionally, whilst change was occurring throughout the post war period, the 1970s and 1980s represented a period a significant development for the integration of people with intellectual disabilities.As we can witness with the case of Nigel Hunt, the parental movement encouraged the self-advocacy movement. This movement continues today and is still working to ensure all people with Down syndrome are recognised as valuable and capable members of society, worthy of our understanding, acceptance and inclusion.

Sophie George is a history graduate from Swansea university, who

wrote her undergraduate dissertation on 'The Changing Attitudes Towards

Down syndrome in Post War Britain'. She is passionate about advocating

for people with disabilities and is seeking a career in the charity

sector.

___________________________References

Ann Furedi (2016): The Moral Case for Abortion, New York.

Dame Eileen Younghusband committee (1974): Living with Handicap, London. Quoted from Philippa Russell (1996): ‘Parents Voices: Developing New Approaches to Family Support and Community’, in Peter Mittler/Valerie Sinason (eds): Changing Policy and Practise for People with Learning Disabilities, London, pp. 73–85.

Peter Grosvenor (1981): ‘Handicap? It was a source of joy for us’, Daily express, 10 August 1981, UK Express Online, https://www.ukpressonline.co.uk/ukpressonline/database/search/preview.jsp?fileName=DExp_1981_08_10_006&sr=1, [Accessed: 05/03/2019].

Linda Sandino (2003): Ann Crosby interviewed by Linda Sandino about her son Matthew who was born in the 1960s with Down syndrome, 26 March 2003.

Paul Hunt (2016): Eileen Clark interviewed by Paul Hunt about advocacy for people with Learning Disabilities in Wales, 12 April 2016.

Maureen Oswin (1973): The Empty Hours: The Week-End Life of Handicapped Children: Weekend Life of Handicapped Children in Institutions, London.

James Wilkinson (1969): ‘The Cruel Hospital’, Daily Express, 28 March 1969, The UK Express Online, https://www.ukpressonline.co.uk/ukpressonline/view/pagview/DExp_1969_03_28_001, [Accessed: 20/04/2019].

The committee of Inquiry (1969): Chapter 3 Of Report On Ely Hospital Individual Complaints Of “Ill-Treatment”, https://www.sochealth.co.uk/national-health-service/democracy-involvement-and-accountability-in-health/complaints-regulation-and-enquries/report-of-the-committee-of-inquiry-into-allegations-of-ill-treatment-of-patients-and-other-irregularities-at-the-ely-hospital-cardiff-1969/chapter-3-of-report-on-ely-hospital/, [Accessed: 20/03/2019].

Wales online (2012): ‘Why the Ely inquiry changed healthcare forever’ (6/02/2012). https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/health/ely-inquiry-changed-healthcare-forever-2041200

[Accessed: 02/06/2020].

Barbara Cole (2012): Mother-Teachers: Insights on Inclusion, Oxford.

Meg Maguire (2006): The Urban Primary School, London.

Len Barton (1997): The Politics of Special Educational Needs, in: Len Barton and Mike Oliver (eds): Disability studies: Past, Present and Future, Leeds, pp. 138–159.

Mary Warnock et. al. (1978): Educational Needs: Report of The Committee Of Enquiry Into The Education Of Handicapped Children And Young People, London.

Mary Warnock (1996): The Work of the Warnock Committee, in: Peter Mittler/Valerie Sinason (eds): Changing Policy and Practise for People with Learning Disabilities, London, pp. 51–60.

Select Committee on Education and Skills Third Report (2006). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200506/cmselect/cmeduski/478/47805.html, [Accessed; 12/03/2019].

Brian Stratford (1985): Learning and Knowing: The Education of Down syndrome Children, in: David lane/Brian Stratford (eds): Current Approaches to Down Syndrome, London, pp. 149–166.

Anne Borsay (2012): Disabled Children and Special Education, 1944–1981. A presentation delivered at the Department for Education.

Nigel Hunt (1967): The World of Nigel Hunt; the diary of a Mongoloid youth, New York.

___________________

Recommended citation:

Sophie George (2020): Parental Advocacy and the Changing Attitudes Towards Down syndrome in Post-war Britain. In: Public Disability History 5 (2020) 2.

Sophie George (2020): Parental Advocacy and the Changing Attitudes Towards Down syndrome in Post-war Britain. In: Public Disability History 5 (2020) 2.