By Meg Roberts

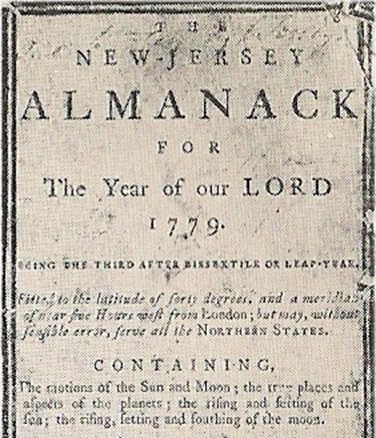

Picture: An example of an almanac of a similar style and period as Daniel George’s. Entitled ‘The New-Jersey Almanack for the Year of our Lord 1779’, printed by Isaac Collins in New Jersey. Image sourced from Rutgers University Library and in the public domain.

In 1775, seventeen-year-old Daniel George, a ‘student in astronomy’ from Massachusetts, composed an almanac. In an eclectic fourteen pages of printed text and tables, he recorded the rising and setting of the sun and the moon, the location of the planets, the tides, the weather, Quaker Meetings, ‘Remarkable Days’, ‘Liberty Days’, and poetry. He also included ‘for the use of the gentlemen officers and soldiers in the American army’ a narrative of the Battle of Concord, recently fought at the outset of the Revolutionary War. George had studied mathematics and astronomy extensively, and the almanac was the result of painstaking calculations throughout the year. In August 1775, George and his father visited the Reverend Samuel Williams, who was known for his interest in astronomy. Seeing the quality of George’s work, Williams forwarded the almanac to Salem printer Ezekiel Russell, including a letter of recommendation.

A shrewd marketer, Russell published George’s almanac in 1776 under the title: ‘George’s Cambridge Almanack … By Daniel George, a Student in Astronomy at Haverhill, in the County of Essex, who is now in the Seventeenth Year of his Age, and has been a Cripple from his Infancy.’ He also printed Reverend Williams’ endorsement, which included further details of George’s impairment. Williams began by noting his initial impression of George as ‘a singular object of pity and compassion’. However, the Reverend noted, ‘with all the disorders of body under which he labors, his mind does not seem to have been at all affected’. Williams went on to recommend the almanac’s publication and praised George’s intricate calculations as ‘equal to other compositions of that kind’ and indicative of ‘rising genius’, despite his ‘singular situation’. He closed his appeal: ‘…if you favour the productions of a Cripple, in the seventeenth year of his age, it must not only give pleasure to him, but to the benevolent and humane who wish success to the ingenious and comfort to the wretched.’

Russell’s choice of title and Reverend Williams’ short narrative places George’s achievement firmly in the context of his impairment, portraying his ‘genius’ as particularly impressive considering his ‘uncommon disadvantages’. Read outside of its eighteenth-century context, this framing of the almanac as the unlikely but remarkable feat of a young man with a physical impairment reads suspiciously like what we would now call ‘inspiration porn’.

The term ‘inspiration porn’ was popularised by the late Stella Young in 2012, first in an article for the webzine Ramp Up and then in a 2014 TEDx talk. She defined the phenomenon as

‘an image of a person with a disability, often a kid, doing something completely ordinary – like playing, or talking, or running, or drawing a picture, or hitting a tennis ball – carrying a caption like ‘your excuse is invalid’ or ‘before you quit, try’ (Young, 2012).

‘Since then, use of the term has expanded to incorporate any media which generally exploits disabled people as objects of pity or condescension to evoke an uplifting moral for the benefit of the non-disabled viewer’ (Ladau, 2019). Ubiquitous across the internet and painfully familiar to the disabled community, these depictions perpetuate a number of harmful tropes.

Caption: Stella Young’s 2014 TEDx talk: ‘Inspiration porn and the objectification of disability’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SxrS7-I_sMQ

The ‘inspiration’ fundamental to inspiration porn usually rests on the assumption that impairment is an entirely debilitating experience. Disabled people’s acts and achievements are therefore framed as automatically exceptional; by living with their impairment they are ‘overcoming’ it. Reverend Williams’ earnest assurance that Daniel George’s ‘mind does not seem to have been at all affected’ by his impairment, and that his almanac ‘seems to be equal to other compositions of that kind’, betrays his apparent low expectations for George’s abilities. Behind his need to convince the reader of the young man’s achievement is a distinct sense of both surprise and marvel – George’s ‘genius’ is all the more remarkable because of its unlikelihood due to his ‘uncommon disadvantages’.

Central to contemporary criticism of inspiration porn has also been the repeated use of disabled bodies to deliver moral lessons and encouragement to non-disabled people. As Stella Young commented, ‘inspirational’ photos and videos of disabled people exist ‘so that non-disabled people can look at us and think "well, it could be worse... I could be that person"’ (Young, 2012). Indeed, her use of the word ‘porn’ in describing the phenomenon was quite deliberate, as its effect is to ‘objectify one group of people for the benefit of another group of people’.

From his repeated emotive references to the ‘wretched’, ‘distressed, ‘unhappy Cripple’, it is clear that Williams was keenly aware of the marketable potential of George’s work – not simply due to its merit, but because ‘the singular situation of the author, bids fair to engage the popular attention’. Part of the novelty of the almanac, regardless of its quality, was in the fact that someone with a physical impairment had written it. This clear objectification of George’s impairment for the sake of intrigue is a starkly reminiscent of inspiration porn, where disabled people’s stories and achievements are exhibited for the benefit of an audience that is assumed to be non-disabled. Reverend Williams actually appeals directly to a readership of the ‘benevolent and humane who wish success to the ingenious and comfort to the wretched’, creating a clear distinction between the charitable able-bodied audience and the impaired object of their compassion.

To a twenty-first-century reader, all too familiar with the tropes of inspiration porn, Williams’ portrayal of Daniel George seems to tick all the requisite boxes. But put back in its eighteenth-century context, it becomes slightly more nuanced. There have been countless intricate changes in the cultural depiction of impairment through history, not least in the last two hundred and fifty years. Most of the historical processes that converged to create both the phenomenon of inspiration porn and the wider disability/ability binary would have been alien to Daniel George and Reverend Williams.

In eighteenth-century North America, the clear distinction between ‘ability’ and ‘disability’ that inspiration porn rests upon had not yet solidified. Historians of impairment in early America have engaged with the social model of disability to explore how cultural constructions of incapacity manifested in this period. They have noted that, though the word ‘disabled’ was often used in the eighteenth century, it did not become a defined or comprehensive social category in the United States until at least the early nineteenth century. This is not to say it was a ‘golden age’ for people with impairments. Daniel George’s physical condition clearly affected his experiences and interactions, and some harmful connotations accompanied the other emotive labels Williams gave him. However, in the eighteenth century an individual’s physical health was always vulnerable and the line between physical capacity and incapacity was tenuous. It was an era of debilitating epidemics, rudimentary sanitation, harsh climates, dangerous labour and an ever-changing medley of medical practices. George’s New England audience may not have read about him and thought ‘well, it could be worse... I could be that person’, because their own day-to-day experiences of precarious health did not induce them to distinguish so drastically between disabled and non-disabled bodies.

The intended purpose of Reverend Williams’ endorsement is also crucial here. Though his wording is emotive and emphasises the peculiarity of George’s ‘uncommon disadvantages’ and ‘rising genius’, this was a fairly standard tone for a patron advocating for a protégé in need of financial support. Most eighteenth-century readers were familiar with various forms of physical impairment due to their everyday involvement in practical and financial support networks for local families, individuals and even strangers. Poor relief in the colonial era was based in the community, and routinely involved provision for people with illnesses and impairments who were partially or wholly unable to labour. Their livelihoods were often a mixture of sponsorship from the local government or private charity, with local churches frequently responsible for the collection and distribution of aid. It was therefore fairly usual for church ministers like Williams to appeal to a community’s sympathies and sense of religious moral duty to gain financial support for a local person in need. George himself thanked his ‘public-spirited Friends and Countrymen’ for purchasing his almanac because they were ‘helping one who is not able, or perhaps ever will have it in his power to help himself’. When Williams and George addressed the almanac’s readers, they did so not to ‘inspire’ a non-disabled audience, but to generate a livelihood.

Furthermore, the devaluation of disabled people’s achievements that runs through inspiration porn was configured differently in the eighteenth century. The flexibility of the household economy and interdependency of local communities, especially in rural areas, often allowed early Americans with impairments to participate in various forms of labour adapted to their needs. Indeed, intense cultural expectations of industriousness from every member of a community required that people with impairments be seen to make some effort to use and develop their skills for the benefit of themselves and the community. George’s almanac was not impressive to Williams because it was ‘inspiring’, but because the young man was clearly conscious of his physical limitations and embracing an alternative avenue by which he could contribute to his community.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the almanac diverges from the contemporary standards of inspiration porn because Daniel George himself is not voiceless. Inspiration porn relies on the silence of the disabled object of inspiration. Listening to the perspectives of actual disabled people complicates the narrative that physical impairment is a terrible burden that people are bravely enduring every day. George is still somewhat constricted by the conventions of appealing for financial support within a deeply hierarchical eighteenth-century society, which required gratitude and deference to patrons. But after Williams’ introduction, George takes over with a page of prose and another twelve pages of astronomical calculations, an account of the Battle of Concord and a variety of monthly readings, important historical events and notices.

This is a rare direct account from an eighteenth-century American with a physical impairment, which makes it all the more significant that George barely mentions his condition. Once he has thanked Reverend Williams and the printer Ezekiel Russell, and acknowledged the help that his ‘kind and generous Patrons who may venture to expend four pence’ would provide, he moves swiftly on. He describes in detail the ‘other excitements’ that may be more interesting to his New England readers than his impairment: the ‘heroic deeds of your brave and renowned Countrymen who so remarkably distinguished themselves in the late Battle of Concord’. For the remainder of the almanac, George is concerned only with providing calculations and observations ‘at least as useful and entertaining as any studied by Gentlemen of more riper years’.

Daniel George’s almanac proved so successful that Russell printed a second edition with additional material. The following year, he composed a new almanac for two further printers in Boston and Newburyport. Between 1776 and 1787, George’s annual almanacs were distributed widely in towns across New England. His physical impairment never seems to have been mentioned beyond the first issue. George eventually moved to Maine and became a printer himself, as well as a schoolteacher and the owner of a small bookstore. In 1800, four years before his death, he became the sole owner of a Maine newspaper (Griffin, 1874).

Eighteenth-century disability history can be tricky to navigate. Many of the concepts and discourses generated by disability studies and disability activism – like inspiration porn – naturally engage with contemporary disabled experience. With this conceptual grounding, it can be easy to accidentally transpose modern concepts onto historical actors who would not recognise them. At first, Reverend Williams’ introduction to Daniel George’s almanac reads like a clear eighteenth-century manifestation of a twenty-first century phenomenon. But where this comparison falls short, we can see the areas where George’s experience did not structurally or culturally resemble contemporary experiences of disability. Inspiration porn, like so many other aspects of the modern disabled experience, is evidently a cultural choice rather than a historical constant.

Meg Roberts is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, researching disability and caretaking during the American Revolutionary War.

___________________

References:

Altschuler, Sari, and Silva, Cristobal, ‘Early American Disability Studies’, Early American Literature 52, no. 1 (2017), 1–27.

Blackie, Daniel. ‘Disabled Revolutionary War Veterans and the Construction of Disability in the Early United States, c. 1776–1840’, Doctoral Thesis, (Helsinki, 2010).

Daen, Laurel, ‘Revolutionary War Invalid Pensions and the Bureaucratic Language of Disability in the Early Republic’. Early American Literature 52 (2017): 141–67.

Daen, Laurel, ‘Beyond Impairment: Recent Histories of Early American Disability’. History Compass 17 (2019).

Daen, Laurel, ‘To Board & Nurse a Stranger”: Poverty, Disability, and Community in Eighteenth-Century Massachusetts’, Journal of Social History 53 (2020), pp. 716–741.

George, Daniel, George’s Cambridge almanack, American Antiquarian Society manuscript copy (Essex, 1776).

Griffin, Joseph, History of the Press of Maine (1874), Book Collections at the Maine State Library, p. 36.

Grue, Jan, ‘The problem with inspiration porn: a tentative definition and a provisional critique’, Disability & Society 31:6 (2016), pp. 838-849.

Ladau, Emily. ‘Beyond Inspiration: A New Narrative’. New Mobility (blog), 1 August 2019.

Turner, David M. Disability in Eighteenth-Century England: Imagining Physical Impairment (Routledge, 2012).

Young, Stella, ‘We're not here for your inspiration’, Ramp Up (2 Jul 2012).

Young, Stella, ‘Inspiration porn and the objectification of disability’, TEDxSydney (2014).

Recommended citation: Meg Roberts (2021): Inspiration Porn and Depictions of Impairment in Early America. In: Public Disability History 6 (2021) 6.