A victorious career fighting the French at sea as a Royal Navy officer during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars required a lot: highly specialized seamanship skills, charismatic leadership, absolute indifference to death or injury, well-placed and active patrons, and luck. What it did not require was two arms or two legs.

From 1795 to 1837 at least twenty-six officers survived amputation of limbs damaged in battle and continued in active service, including command at sea. They continued to capture, sink, or burn enemy ships. Six returned to fight without a leg; twenty without an arm (Michals, Lame Captains and Left-Handed Admirals: Amputee Officers in Nelson’s Navy. All statistics and quotations from this source.). All these officers were gentlemen and thus well-positioned within patronage networks. The support offered by their elite social and professional status shaped their experience of limb loss in their day, as did the fact that this loss was not congenital but rather incurred in defense of their country. Today, their distinctive experience shows how socially- constructed disability may be separated from the effects of physical impairment itself.

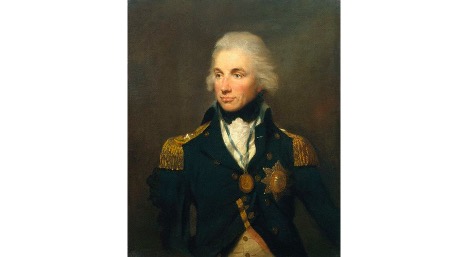

Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson is the most famous by far of these active-duty amputee officers. He lost his right arm in a relatively unimportant fight years before he won the historic engagements that earned him his place on top of an enormously tall column in central London: the Nile (1798), Copenhagen (1801), and Trafalgar (1805). There is only one Horatio Nelson. But as a successful active-duty amputee officer, he was in good company.

The careers of these amputee officers draw attention not only to their particular talents, but also to an institutional culture that allowed their country to take advantage of them. The Royal Navy of the time has an entirely deserved reputation as a ruthless fighting machine. The fact that this ruthless fighting machine needed and valued amputee officers should make us question ableist assumptions about who is fit to serve, and in what capacity.

Promotion: "An Additional Claim"

We might assume today that only a wartime scarcity of officers made such careers possible. However, the opposite is true. Amputee officers won the privilege of continued command despite fierce competition, not because of a lack of candidates. Although the Navy of their day was chronically short of seamen, it was oversupplied with officers. There were far too many talented and ambitious officers begging for the privilege of command, and far too few ships to accommodate all those whose patrons bombarded the Admiralty with letters pressing their cases.

Such letters portray an amputee officer’s limb loss as “an additional claim” to the privilege of command. For example, on April 13, 1809, Captain Duncan of the Mercury stressed this point when writing to the father of his First Lieutenant, Watkin Owen Pell, after a successful action: “His having before lost a Leg in the service will give him an additional claim & I have no doubt the Lords of the Admiralty will take into consideration his sufferings & reward his Gallant services.” Pell was promoted to the rank of Commander on March 29, 1810, won further battles at sea, advanced to post-rank on November 1, 1813, and eventually reached the rank of admiral.

Limb loss, then, was a distinction that moved an amputee towards the front of the host of officers hoping to go back to sea, rather than sending him to the back of the queue. Losing an arm or leg under the specific circumstance of a successful battle could be an advantage in the competition for promotion, It formed part of a career path that was unusual, but not unique to the larger-than-life figure of Nelson.

In fact, in Nelson’s Navy, the meaning of “able-bodied” was itself different than what we might assume today. It referred to a certain set of skills, not a certain kind of body. Every man who signed on to a ship’s books was given a rating based on his experience. Those new to the sea were called Landsmen, those with limited experience were Ordinary Seamen, and those with at least two years at sea, and specialized skills gained through this experience, were rated Able Seamen or Able-Bodied Seamen, often abbreviated to A.B. Based on skills not bodies, a person with limb loss could be deemed “able bodied.”

Self-Presentation: "See, Here Is My Fin!”

There was also a performative element to how these amputee officers managed other people’s perception of their bodies. People who live with a visible physical difference today often describe the additional everyday task of assuring potentially skeptical onlookers that they are competent rather than conforming to stereotypes of disability.

By their continued careers as national heroes who commanded men, ships, and a great number of large guns after limb loss, these amputee officers disrupted stereotypes of their day that linked physical difference to pity and charity, or to the monstrous and evil. The fact that they were officers also meant these men were very good at being looked at. Part of the job of any successful fighting officer was to stand bolt upright and project confidence in the heat of battle.

There are many well-documented examples of Nelson incorporating his impairment into his public image. On one memorable occasion, when challenged by a ship in the Baltic in 1801, he threw back his boat-cloak and declared “I am Lord Nelson. See, here’s my fin!”

Admiral Sir Michael Seymour was one of Nelson’s fellow amputee officers, although he is not widely known today. He had lost an arm in battle, but also carried his displays of competence into civilian life. He had a wife who was “devoted to her garden” and, at home, he often “could be seen on top of a ladder, pruning a vine or restraining a vigorous creeper, to the wonder of his younger children, who marveled that one who had but a single arm could attempt such work and indeed, he surprised many by what that on hand and arm could accomplish.” In addition to surprising onlookers by accomplishing tasks such as pruning, dealing cards, and carving roasts one-handed, Seymour and his good friend Admiral Sir James Alexander Gordon gave a kind of public performance of mock-pity. Gordon had lost a leg in battle early in his distinguished career. Seymour’s biography includes an anecdote in which Seymour and Gordon carry on a “humorous dispute” before an audience of their friends “as to which was the better off, he who had lost an arm or he who had lost a leg, each maintaining his own loss to be the lightest.”

Portraiture: Looking Like a Hero

We also can see deliberate self-presentation in these officers’ portraits. Eighteenth-century painter Sir Joshua Reynolds’s enormously influential Discourses on Art (1769-1790) requires the artist to make a hero look like a hero: “a painter of history shows the man by showing his action…He cannot make his hero talk like a great man; he must make him look like one.” For Reynolds, only a certain kind of body can make human greatness visible. A hero must not be “lame or low”: “Alexander is said to have been of a low stature: a painter ought not so to represent him. Agesilaus [a king of the ancient Greek state of Sparta] was low, lame, and of a mean appearance. None of these defects ought to appear in a piece of which he is the hero.”

In keeping with these principles, an officer’s loss of an arm was not usually represented as part of his heroic image. Rather, the portraitist more often resorted to the “discreet three-quarters view,” as in Sir Peter Lely’s dual portrait of Sir Frescheville Holles and Sir Robert Holmes. Holles brandishes a sword at the viewer, standing at an angle that conceals the fact that his other arm was lost in battle.

| |

| Figure 2 - Peter Lely and Sir Frescheville Holles. Credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. |

This all changed with the growing fame of Horatio Nelson. Nelson was the subject of more formal portraits than any military hero except the Duke of Wellington, and he presented the viewer with a full-frontal view of an amputee. Lemuel Francis Abbott’s much-reproduced 1797 portrait of Nelson foregrounds the empty right sleeve of Nelson’s Royal Navy rear admiral’s uniform, neatly secured across his chest, the cuff angled up to point towards the gold star of the Order of the Bath:

|

| Figure 3 - Lemuel Francis Abbott, Horatio Nelson (1797). Credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. |

Nelson’s celebrity status seems to have popularized this pose for officers who had lost an arm. Michael Seymour is among those who chose to be represented in this way. Here is an engraving of James Northcote’s portrait of Seymour:

|

| Figure 4 -James Northcote (engraved by James Cook), Michael Seymour. Credit: National Portrait Gallery. |

Nelson’s popular image as an amputee admiral remained constant even as memories of wartime service faded and Victorian ideas about disability grew more popular. However, the image of other amputee officers shifted, leaving Nelson to stand alone. For example, a later engraving alters Northcote’s portrait of Michael Seymour: it draws in the left wrist and hand that Seymour lost in battle.

|

| Figure 5 - Admiral Sir Michael Seymour, wrist restored. Credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. |

By recovering the careers of these amputee officers as a group, I do not mean to suggest that the Navy of their day was a utopian space for physical difference in general. I do mean to suggest, however, that for men in a certain social and institutional position, certain kinds of physical difference were an everyday part of professional life at a time when we might assume otherwise.

Teresa Michals is an Associate Professor at George Mason University. Her publications include Books for Children, Books for Adults: Age and the Novel from Defoe to James (Cambridge, 2014) and Lame Captains and Left-Handed Admirals: Amputee Officers in Nelson's Navy (University of Virginia Press, 2021). She studies the history of disability, children's literature, and 18th and 19th-century British novels.

_____________________Recommended citation:

Michals. Teresa (2022): "An Additional Claim": Amputee officers in Nelson's Navy. In: Public Disability History 7 (2022) 5.