In the countryside, an hour’s train ride away from the noisy central districts of Tokyo, the buildings of Takinogawa Gakuen stand in solitude, surrounded as they are by deep forest and tiny streams. As a social welfare center, Takinogawa Gakuen provides services to people with mental disabilities. The small institution has a long history. Visitors learn with a sense of surprise that this first institution of its kind, which was established in Japan more than a hundred years ago, continues its mission on the western outskirts of the metropolis.

In the past ten years, the field of disability history has been expanding hugely to include various areas of research from diverse perspectives. No historian can now ignore the critical importance of disability, which influences one’s social life, at the intersection with other social attributes such as race, gender, and class. To this current state of the field, the story of Takinogawa Gakuen and its founder Ryoichi Ishii will add another new viewpoint: a transnational perspective on the history of disabilities. What it means to be disabled varies with location. But historical inquiries reveal that different institutions of disability in various localities have often developed through transnational exchange of ideas and practices beyond borders.

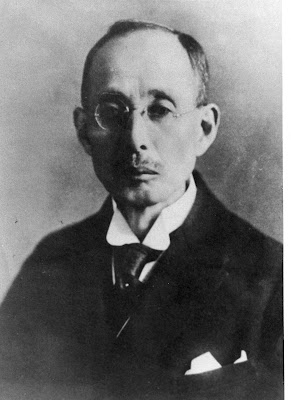

|

| Portrait of Ryoichi Ishii (Courtesy of Takinogawa Gakuen) |

During his research travel, Ishii diligently absorbed Western scientific ideas on mental disability at various institutions in the United States. In Massachusetts, he learned the latest knowledge at the Boston Public Library, while auditing lectures at Harvard University. During his stay in Cambridge, Ishii also had the opportunity to meet Helen Keller. For on-site study of institutional operations, Ishii visited several prominent schools and asylums, such as the Minnesota School for the Feeble Minded in Faribault, the Massachusetts School for Idiotic Children in Waverly, and the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble Minded Children in Elwyn. In Orange, New Jersey, Ishii visited the school founded by French educationist Edward Seguin, for whom Ishii had a high regard as “a giant in the field.” In December 1896, Ishii returned to Japan. With his newly acquired knowledge, he reorganized the former girls’ orphanage into Takinogawa Gakuen School for Feeble Minded Children in 1897.

At the very time when Ishii was visiting institutions in the United States, the idea of “mental retardation” was in fact undergoing a significant change within American scientific circles. Until the late nineteenth century, the understanding of intellectual disability as a defect that was partially curable through proper training of the nervous system had dominated scientific discussions under the influence of Edward Seguin’s physiological theory. With the rise of the eugenics movement at the turn of the twentieth century, however, American scientists came to believe “mental retardation” to be an incurable hereditary impairment. Asylum superintendents upheld the idea of permanent segregation of the mentally disabled as a menace to society. Old physiological understandings of “idiocy” gradually gave way to a new psychological measurement of “feeble-mindedness.” It was the chaotic mixture of old and new theories in this transitional period that Ishii learned in the United States and brought back to Japan.

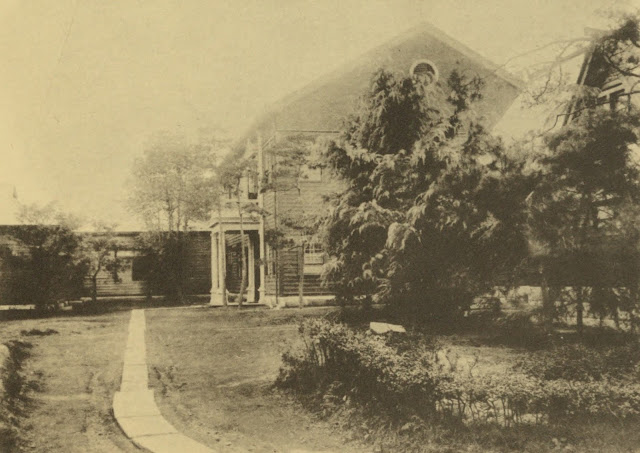

|

| Takinogawa Gakuen in the Early Twentieth Century. Source: Bureau for Social Work, Present Conditions of the Child Welfare Work in Japan (Tokyo: Home Department, 1920). |

Not just transplanting American ideas of mental disability into Japanese society, Ryoichi Ishii and his experiment at Takinogawa Gakuen paved a unique path for the institutional care of the mentally disabled in Japan. By the end of World War II, the Japanese government had assumed practically no legal responsibility for the care of people with mental disabilities. The care for the mentally disabled rested on desperate efforts by a handful of private institutions. In a letter to Martin W. Barr, the chief physician at the Pennsylvania Training School in the United States, Ishii wrote, “A new building is just going to be finished, and twenty more of the feeble-minded are expected next month. There are nearly two hundred applicants, but I have no room for any addition of inmates. My institution is a private one.” In the absence of state custodial care as found in the United States, Takinogawa Gakuen and its follower institutions gradually enhanced their practical capacity. In the 1950s, the growth of these private institutions gave basis for the introduction of the public-private partnership system, which has characterized public assistance for people with mental disabilities in Japan up until now.

References

- Ishii Ryoichi Zenshu Kankokai, ed. Ishii Ryoichi Zenshu. 4 vols. Tokyo: Ozorasha, 1992.

- Takinogawa Gakuen, ed. Takinogawa Gakuen Hyaku-Nijunen Shi. 2 vols. Tokyo: Ozorasha, 2011.

Recommended Citation

Yoshiya Makita (2016): Disability History Beyond Borders: The Story of Ryoichi Ishii and Takinogawa Gakuen in Japan. In: Public Disability History 1 (2016) 12.

Yoshiya Makita (2016): Disability History Beyond Borders: The Story of Ryoichi Ishii and Takinogawa Gakuen in Japan. In: Public Disability History 1 (2016) 12.