I am told that I lost my eyesight during the seventh month of my life. I was educated in boarding schools, in schools specially for the blind, and in public schools. I taught the blind when I was still living in Palestine, where I was born in 1929, when I lived in New York City, when I worked in Kuwait; and I hold a master’s degree in special education. Still, I should be embarrassed to admit that studying in a scholarly fashion the phenomenon of blindness (“disability”) has never seriously interested me. I have a Ph.D. in English Literature from New York University, and I taught literature for some thirty years. I am now a retired professor emeritus. I have enjoyed poetry all my life, writing it in Arabic when a child and later in English. I may say I have used poetry to react to all things that have interested me including, of course, the phenomenon of blindness, not academically, but as a poet. I have lived with blindness all my life, and have become accustomed to the ways and means, so to speak, of the phenomenon. To a large extent this “disability”, then, is only one of the phenomena of ordinary life, to be dealt with as an aspect of life, with, if you like, what most sighted people would judge with special consideration. I have lived so long with the phenomenon. I do not consider it special.

|

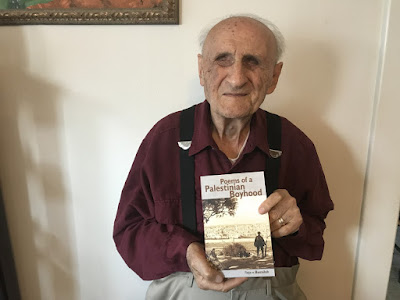

| Reja-e Busailah with his latest publication Poems of a Palestinian Boyhood. |

As I have said, I am a poet. I am a poet first and foremost, and my poetry is a reaction to as many phenomena of life as I am aware of: personal and general, emotional, social, political, and so forth. Needless to say that all these phenomena interact and influence each other. They give to each other and take from each other. My poetry deals with all of this and more. I write poems about blindness with as much comfort as I would write poems about “the honeysuckle, that divine commoner”, the call of a bird, the behavior of a politician, or the face of a girl as conveyed to me by her voice. Yet they are poems which, in a sense, focus on a specific phenomenon, the phenomenon of blindness, some directly, some not so directly, while still others deal with the theme from quite a distance. Moreover, these poems are all taken from a manuscript, Poems Out of Sight. Blindness, in one way or another, to assert once more, is in each of my poems, though none of them was written with the purpose of exploring the theme. They were written only in response to the dictation of the circumstance prevailing about the time of the writing.

Let me comment on a specific aspect of the many consequences of blindness. Much of the experience an ordinary blind person gets is through the ear, through sound and through the complexity of sound which produces the word. Space does not allow here for an at length discussion of touch. The blind person hears of a vast field and of a limitless sky, and the acquisition of this experience does not stop with hearing. The blind person has been given the word, and words are pregnant with concreteness and an infinity of growth, concepts, and connotations. Thus a word becomes the repository and vehicle of our intellectual growth, of civilization itself. A blind person, then, has the benefit of the word. Blind people are capable of participating in most of the social activities of the sighted. You find them engaged in all sorts of activities theoretical and practical, scientific, technical, and philosophical, in education, in politics, and so forth. I cannot forget the two blind men in Kuwait who came to learn Braille, the three R’s and so forth while still keeping their job of earning their daily living. After class or before it, they would swim to anchored ships to bring ashore in large leather sacks the sweet water the country needed then. This is why segregating the blind from the rest of society is a bad mistake. Integrating them with the rest of society is very beneficial to both.

|

| Reja-e Busailah reading poetry for his YouTube channel. |

Let me select only a few of the manifestations of the interaction between blindness and the world of sight or society as I have experienced it in action and in reflection. I will present the examples of these manifestations only as they are treated in my poetry. Blindness in the poems is not primarily the focus. The focus is on the poem and only an aspect of the phenomenon is used or mentioned, sometimes seriously, sometimes humorously, and so forth.

It has long been held that blindness is a mystery with supernatural roots and origins. Blindness is a curse or a blessing from God or from some mysterious power. Two superstitions emanate from this in “The Four Branches”: the husband who opens the day with rage and anger on glimpsing a blind person crossing his way, and the wife who ends the day pleased and contented because the blind person is the first to enter her store, which brings her so much business this day long. The blind person is aware only of

the morning greeting

of the sapling of a child

[which] reaches the blind ears,

hesitant yet resolute,

unaware of the cares of sight,

innocent of the confusion

on the awakening of the soul.

In “Journey of a Curse”, this attitude is given a clearer expression. The blind child throws a rock at the old man, who responds by

he panted up the hill,

he paused at what he saw,

he cursed under his breath:

“No wonder God smote you blind!”

He spat on his left,

his footsteps echoed into the dusk.

At the end of the poem, though, the blind boy has acquired some education, and is able to repeat to his interlocutors:

“When man is good,

he is higher than the angels;

when he is not good,

he is lower than the beasts.”

The couple listened with wonder and humility,

“God blessed the blind for reasons

man’s ken may never probe!”

In “Virgil and Beatrice”, the emphasis is on something that happens pretty regularly everywhere, and on the humor with which it is treated:

So normal was that day,

“normal,” you know what I mean

that you couldn’t but think of the cliché

which pops up into the blind mind’s remembrance

upon such a day:

“Does your dog bite?”

“You bet he does.

Virgie would love to have a hunk

of your flesh for his dinner!”

After all, if it had to be so,

let it be him, not me!

I would be lying,

if it were the reverse.

Or upon another such day:

“What’s your dog’s name?...

Isn’t he adorable?...

He’s your best friend, isn’t he?”

“To tell you the truth, he isn’t.”

This bemused the poor woman,

shocked her into a strange silence,

staring as a blind man thought

until he enlightened:

“Betty is my best friend,”

touching his wife’s arm.

After all, wasn’t she the one

who was going to pacify his hunger that night?

“To Whom” is a commentary on factual events pretty common in life and quite similar in sound, and shall I say, looks too. The poem concentrates on violence. The blind child is a member, an essential member, of a community similar in fate and the workings of fate. The dog is helpless while being clubbed to death because he is tied. The blind child (actually the author) is lashed and lashed until his feet are bloodied and swollen when he is thrown on his back with his feet gripped tight. The girl is also held down on her back with the boots of two men on her hands, “that the third may thrust and thrust and thrust,” while the AK-47 is impatiently waiting to complete the job. Now, the fate of these three is the same as the fate of Palestine when Great Britain for thirty years held the people violently down in order to give the country to the foreigners. And this she did with great success, accompanied by dark horrors either unknown or wantonly ignored.

The speaker knows (mentally) that his wife sees with her eyes in the poem “Her Eyes.” But he does not see. How does he circumvent the frustration?

If the sound of her voice is the spark

which puts out the old stars, which inflames the dawn

and makes thirstier with the dew the beams of the sun

forever young

forever old;

if the sound of her voice is the start

which ripples through the day

hour by sparkling hour

and tipples in the bright and the red

before it comes ashore;

if the sound of her voice is the birth and the breath

and the pulse in the soul

and the spirit of the pulse—

I wonder what is left for the light of her eyes!

Far-fetched? Maybe, but there is an adequate substitution for the absence of sight, however subjective or arbitrary it may be. Sound, or the word here, has supplanted sight. In “Two Airs”, you may say the picture is reversed. The author would perhaps paint the sound of the cardinal were he not blind. Instead he imagines a parallel to the sound of the cardinal. Here the two songs of the bird resemble two objects, the carnation standing on its stem and a flourishing bell:

Two airs of a cardinal

(he has quite a few in his repertoire)

a cardinal who is either fully oblivious

to the world, or wholly of it.

Like children scaling up and down a fragrant dream,

one air scales up

the other scales down

the length of a white carnation

standing on its stem,

An air flushed starting downward

from the brim of a cup of sunlight,

another blushing as it flourishes

upward towards bell’s bloom.

Again, this may sound too far away from the “disability” blindness. All the same, blindness remains related to the poem. “A Note on Touch” best exemplifies the highly subjective, arbitrarily subjective, treatment of something physical with imagery acceptable perhaps only to its author. One aim is to reject the attitude among the sighted that touch replaces vision. Space is too narrow for discussing the poem at length.

The face of the sick child shocks the mother,

she sees it as a hard-boiled egg!

The child runs a blind hand

over the face of the peeled egg,

it is smooth and soft, it is delightful:

Touch, therefore, when shielded from the representations

of the sense of light,

grows its own garden of realities,

solid facts

as a matter of fact,

anchored outside the domain of vision.

The fallacy, therefore, of assuming

that hand and eye are relatives

only breeds the falsehood that the dynamics

of, say, a fish’s mouth

in either’s hold are similar

if not the same;

(but let us first dispose by way of footnote

of the man who out of touch with sight

once marveled greatly at the marble mouth1

all misled by its smoothness from its severity,

or of the goddess of beauty who short-touchedly

mated with a bandy-legged bore2):

to the touch pure and free

the mouth of that primary beast

becomes a mermaid’s

transported into a summer’s nigh-haze

composed of mist-moistened sun,

and a vase in her hand

gleaming through the morning

the special mouth beaming

as on a crystal range

the clarinet’s scale in bloom—

visual sensibility tamed fantastic

if you like by the alchemy of touch.

Blindness then is the deprivation of sight. In such poems as we have just mentioned mixed imagery is resorted to, not perversely, but in reaction to the pressure of necessity. The visual experience which is absent here is expressed by, or translated into, the experiences of the remaining faculties. It is hoped that this arbitrariness is still compensated for by these new experiences. But it is the reader who will have the ultimate judgement on the treatment of the theme in the poems as well as their artistic quality.

The “disability” of blindness, then, occupies much more of the human concern than do other disabilities. As we have seen, this is due to the nature of the impairment of the disability. It so lends itself to varieties of interpretations, expansions, modifications, and so forth. No wonder, then, that Jose Saramago devotes a whole novel to blindness as a metaphor in which a whole city goes blind.

|

| Reja-e Busailah accepting the Palestine Book Award for Best Memoir 2018 in London. |

Reja-e Busailah’s latest publications are In the Land of My Birth: A Palestinian Boyhood (Institute for Palestine Studies 2017), winner of the Palestine Book Award (2018) and Poems of a Palestinian Boyhood (Smokestack Books 2019). He enjoys sharing his poetry with others especially reading his poetry on his YouTube channel.

________________________________

Recommended citation

Reja-e Busailah (2019): On Blindness in Poetry. In: Public Disability History 4 (2019) 10.