By Emmeline Burdett

A couple of weeks ago, I saw a charity advertisement which discussed a young autistic man who painted, allegedly because he found it ‘therapeutic’. I felt that this was a rather patronising comment, because, whilst many people find painting therapeutic, the advert’s use of the word in connection with the (frankly unnecessary) information that the young man was autistic, seemed to imply that it did not matter whether he was any good at it or not, when, from the evidence of his paintings, he was extremely talented. The assumption that one is not really any good at anything is something that often dogs not just disabled artists, but disabled people who do anything – particularly if what is being done is unusual or unexpected. This experience of unreasonably low expectations is something which makes it possible to identify not just with disabled people (and, obviously, with other people) who are subjected to this in the present, but also with those who encountered similar attitudes in the past. One of these people was the nineteenth-century English artist William Henry Hunt. There was an exhibition of Hunt’s work at the Courtauld Gallery in London in 2017 – entitled Country People - and in Hunt’s case, it was his uncle who apparently believed that he was apprenticed to an artist merely because his family were at a loss to know what to do about him:

"Little Billy Hunt was always a poor cripple, and … as he was fit for nothing, they made an artist of him." (Roget 1891: 192)

Just as I criticised the charity advert I mentioned above for implying that if one is disabled, something for which one has obvious talent can only have a "therapeutic" purpose, so it may be that Hunt’s uncle (who was a butcher), believed that something like art could only really be a hobby, and that as his nephew was physically unable to take up a "real" occupation (such as a butcher?), he had to do something rather less important.

Butcher, baker, candlestick-maker….artist:

William Henry Hunt was born near Covent Garden in London in 1790, and in 1806 he was apprenticed to the watercolourist John Varley. Hunt had been disabled from birth, with one description of him saying

"He was a sickly child, his legs being weak and puny and his knees and toes turned in so that he could only walk with difficulty and had to shuffle along." (Witt 1982: 31)

He joined the Old Water-Colour Society in 1825, and exhibited almost 800 works there. Many of the paintings in the Country People exhibition also dated from the 1820s, and this includes

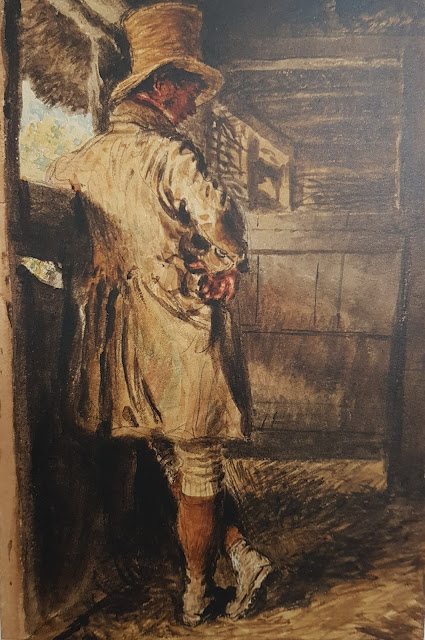

Farmer in a Barn (1820), which is a very good example of the position in which Hunt painted – his disability meant that he painted sitting down, and in this instance he was behind his sitter.

Farmer in a Barn (1820), which is a very good example of the position in which Hunt painted – his disability meant that he painted sitting down, and in this instance he was behind his sitter.

|

| Farmer in a Barn. Watercolour over traces of graphite, 274 x 182 mm Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery James Leslie Wright Bequest, 1953 JW 271 |

Cassiobury Park

Hunt’s two major patrons were the Duke of Devonshire and the Earl of Essex. He met the latter when he was on a sketching trip near the Earl’s home – Cassiobury Park near Watford in Hertfordshire. After Hunt began working for the Earl of Essex, he often sketched outdoors, and

"in the woodlands of Cassiobury, William Hunt used to be trundled on a sort of barrow with a hood over it, which was drawn by a man or a donkey, while he made sketches…." (Ibid.: 40).

Many of the models for the Country People paintings actually worked on the Cassiobury Park estate – for example, the sitter for The Head Gardener (c.1825) is thought to have been the Earl of Essex’s head gardener, while a photographic reproduction of The Gardener (also c.1825) records that the original drawing was given to its model, Thomas Hainge, who worked at Cassiobury Park in various capacities for most of his adult life. The gardens at Cassiobury Park had been famous since the end of the eighteenth century, and in 1832, the German nobleman and landscape garden expert Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau had written admiringly of their hot-houses, which were used for growing all kinds of fruit, such as pineapples, peaches, nectarines, melons and grapes. Another important model was Hunt’s wife Sarah, who makes an appearance in several of his paintings, including The Kitchen Maid (1833) and The Orphan (1848).

Hunt and Art History

Hunt has been described as "one of the most neglected and under-documented watercolourists of the nineteenth century" (Ibid.: 25f.) but in his day, he was both well-known and influential. The artist and art critic John Ruskin admired Hunt, and was taught by him in 1854 and 1861, and Hunt himself invented a technique which enabled him to get "amazing bloom" on the fruit that he painted, meaning that it looked extremely vibrant and lifelike. Hunt achieved this by mixing gum with Chinese White as a hard primer, then painting in watercolours.

Hunt and Disability History

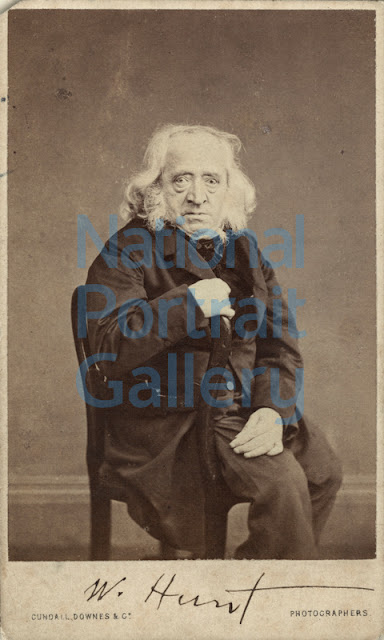

Both the Country People exhibition and the small amount of existing scholarship on Hunt portray his impairment in terms of an individual limitation. Though the Country People catalogue looks at Hunt’s work in terms of the development of the portrayal of "country people" in art, its only real acknowledgment that Hunt was a disabled artist comes when discussing individual paintings (like the above-mentioned Farmer in a Barn) and the effect that Hunt’s impairment had on their composition – there is no discussion of disabled artists over time and of how Hunt might fit into this. The catalogue description accompanying Hunt’s painting The Stonebreaker (1833) suggests that, being disabled and without high social standing would have meant that he "surely empathised with the less privileged members of the rural community". (Selborne/Payne 2017: 58) Curiously, Hunt is not really a figure in disability studies either. This is particularly odd, as it is quite obvious from photographs of Hunt that his upper body was significantly more powerful than his legs.

|

| Portrait of William Henry Hunt. Copyright National Portrait Gallery. |

That Hunt is not seen as a figure within disability studies was exemplified by his non-appearance in UK Disability History Month’s 2017 focus on "Disability and Art". UK Disability History Month (UKDHM) began in 2010, and runs from late November to late December annually. Every year, a different theme is chosen (e.g. "War and Impairment"; "Disability and Music", and so on). As part of the 2017 events, the UKDHM website had a section focusing on about fifty disabled artists, and Hunt was absent from this, despite the fact that, a few months previously, there had been an exhibition of his work in a gallery a few miles away.

It’s difficult to say why nothing about Hunt featured in UKDHM 2017 – it could have just been an oversight, as Hunt is not nowadays a well-known artist. Nevertheless, his life does raise matters which are pertinent to disability studies and disability history. As well as the question of Hunt being underestimated, which I discussed above, there is also the matter of his having been quite an idiosyncratic person, despite his very conventional contribution to art history. This unconventionality was expressed in his approach to the teaching of drawing, and his criticisms of the way it was usually taught. (Witt 1982: 57) In addition, Hunt painted a number of black people, and did he do that just because they were there, or did he have some sort of agenda? There is also the question of Hunt being little-known nowadays. Whilst it is too simplistic to announce stridently that this has happened because Hunt was disabled, is this a factor? This last question is quite fundamental: in my view, women’s and minority history (which includes disability history) should enhance knowledge of a collective past, rather than trying to suggest that minority historians are engaged in a completely separate endeavour from that pursued by mainstream historians, or alternatively that we live in some sort of permanent present – in one of the essays in the Country People exhibition catalogue, its author wrote that

"Hunt’s finely-crafted figure studies open a window onto a vanished world of poachers and gamekeepers, millers and maltsters, estate gardeners and labourers." (Selborne/Payne 2017: 11)I feel that it is important to acknowledge that Hunt’s disability was an aspect of his identity, but also to remember that it was an aspect, rather than the whole story. Another question relevant to disability studies is that Hunt’s attitude to his age-related impairments (in later life, he became very accident-prone) seems to have been quite different from his attitude to the impairments that he had always had: in 1863 – a year before his death – he wrote in a letter "How I do wish I were thirty years younger!" (Roget 1891: 199) In this, he might be compared to the disabled eighteenth-century English politician William Hay, who caused some difficulties for modern disability studies scholars because, although he regarded the impairments that he had been born with as part of his identity - as he discussed in his Deformity: An Essay (1754) - he tried very hard to find a cure for the bladder-stone which troubled him throughout much of his adult life.

Emmeline Burdett is a writer and translator.

____________________________________________

References:

J.L. Roget, A History of the Old Water-Colour Society (2 vols.), (London: Longman’s, Green, and Co., 1891), vol.II.

Joanna Selborne and Christine Payne, William Henry Hunt: Country People (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2017).

John Witt, William Henry Hunt (1790-1864), Life and Work, with a Catalogue (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1982).

Recommended citation:

Emmeline Burdett (2021): Not "Fit for Nothing": William Henry Hunt. In: Public Disablity History 6 (2021) 9.