By Owen Barden

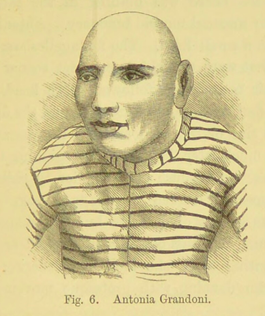

Inside the History of Learning Disability was a 2018-2020 participatory project on the history of learning disability. The project focused on two points in time, the mid-19th Century and the present day. It thus spanned the history of institutionalisation. Although participatory methods are becoming more common in inclusive research, and in learning disability research particularly, it is – as far as we can tell – unique in using this approach with digital archive material. “We” are two teams of researchers who worked on the project. One team was based at The Brain Charity and Liverpool Hope University, in Liverpool. The other team came from the Teaching and Research Advisory Committee (TRAC) at the University of South Wales. The teams were made up of people with learning disabilities, their families and advocates, and academics. One academic worked with the Liverpool team and one with the TRAC team. We used material from a digital archive called the UK Medical Heritage Library to examine the history of institutionalisation of people labelled with learning disabilities. We focused on the life history of one person who was written about in a book in the archive. She was called Antonia Grandoni, and lived in Milan, Italy between 1830 and 1872. She spent a lot of her life in an institution because she was diagnosed as a ‘microcephalic idiot’ (microcephaly means having an exceptionally small head). We used creative methods as well as talking a lot about what we found in order to express what we felt about Antonia, her life, and the way she was treated. This helped us make sense of our own experiences of learning disability, and to learn about each other’s experiences. One of us summed this up very neatly: bringing the past into the future.

This project is important because people with learning disabilities have not often been able to do research about the history of learning disability. They have been excluded from much research, including the historical kind. Historical research has tended to be done by historians and other academics like sociologists. Research about learning disability has tended to be done by doctors and other people in the medical professions, like psychologists. Academic research is not generally noted as being accessible to people with learning disabilities. Although there have been some recent moves to integrate history into critical disability research – perhaps most notably in relation to this project through the work of the Social History of Learning Disability research group at the Open University – such research remains relatively scarce. This means that people with learning disabilities are often excluded from learning disability history research in three ways beyond not being regarded as its audience. Firstly, because they are not involved in producing research, they are excluded from writing about history. Their stories are not valued or listened to. Secondly, prejudice going back centuries means that disabled people – especially those we would now call people with learning disabilities – are often absent from official historical records. They are simply missed out because other people thought they weren’t important. Thirdly, archives tend to be difficult to access. There are usually many barriers. For example, many historical records are still only available in their original physical form, on paper. This means travelling to where they are kept if researchers want to see them, which can be difficult. Rules about confidentiality can also prevent access to things like hospital and asylum patient records. The old-fashioned language and handwriting can make historical material difficult to understand. Archivists and other guardians of historical materials can also be very protective of them. This is understandable, because they can often be sensitive, rare and fragile, but it does present a barrier to accessing the material. However, the recent trend towards digitising archive materials is helping to remove some of these barriers – although the UKHML is not very accessible to most people.

The UKHML a huge collection of over 66,000 19th Century history-of-medicine texts. It has full colour images, pdf downloads, and Optical Character Recognition of the full text of all the publications it contains. It is a very important and useful resource. However, there are barriers to access to many people. Firstly, the sheer number of available texts is potentially overwhelming. Secondly, it has been set up with medical historians in mind, and is organised accordingly. For instance, when entering the archive you are invited to search either by Body Parts or Medical Conditions. Thirdly, because of the nature of the material much of the language is both old fashioned and very technical. Using modern search terms such as “learning disability” does not yield very helpful results. It is better to use the old diagnostic labels like “idiot” or “imbecile”, but even after extensive filtering a researcher is still faced with thousands of texts to choose from. As an academic, I initially worked alone to find and select a text. The book chosen was On Idiocy and Imbecility, published by Dr William Ireland in 1877. The book contains Antonia Grandoni’s case history. There is a descriptive account, two pencil portraits, and tables of her anatomical measurements. The history has been pieced together from the reports of doctors from Milan, where she lived with her family before being institutionalised in a hospital for an undisclosed period up until her death in 1872, at the age of 42. Various elements of her case history made it ripe for analysis and so it was chosen for the second, participatory step, which would aim to rediscover and re-interpret Antonia’s story for the present day.

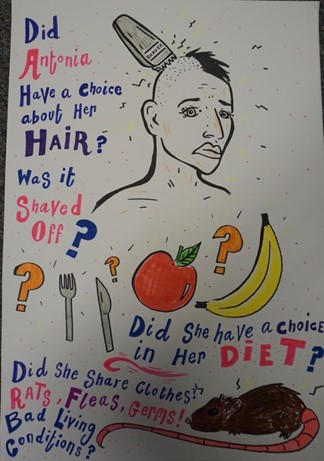

The Liverpool team and the TRAC team then each ran a series of four two-hour participatory workshops. The aim of these workshops was to analyse Antonia’s story, with a view to understanding attitudes towards learning disability in her own lifetime, and to relate her life to the lived experience of learning disability today. In the early workshops, the teams focused on collectively analysing and interpreting Antonia’s case history. After analysing Antonia’s story, we moved to more creative methods in order to respond to her story and make connections to the lived experience of disability today. Both teams were facilitated in this by graphic illustrators. A full account of the methodology can be found here.

Our key findings were that although people talk about inclusion, and think they are more inclusive these days, many of Antonia’s experiences seem very similar to what people labelled with learning disabilities often encounter today. These include discrimination, segregation and dehumanisation. For example, despite being described as ‘fond of learning amorous poetry’ and having ‘erotic tendencies’ Antonia was seemingly denied any kind of romantic relationship, an experience that resonated with many older learning-disabled team members. Despite this, and some of the harrowing stories that were told (including experiences of sexual abuse, forced medication and sexual assault) another important finding was that we very much enjoyed doing the research. As well as finding out about the history, we learned new skills, some of us grew in confidence, and we also made new friends. After the main workshop series was complete, we held Zoom meetings to explore how the project had affected the people involved. They were asked to give one word which summed up their experience of the project. The words they gave included: Enlightening, Powerful, Very Interesting, Truthful, Inspiring, Joyful, Fascinating, Fun, Challenging, Transformative, Amazing, & Very Moving.

People felt privileged to have the opportunity to tell their own stories, be listened to and understood, and to listen to others’ stories. Many people spoke about how they had grown in confidence and were more willing to try new things and to express their ideas and opinions. For example, one person said he was terrified before the first workshop and almost went home without getting out of the taxi, but now thinks it’s one of the best things he’s ever done. Several TRAC researchers felt able to participate in another study about the impact of Covid-19. Others spoke about how the research methods used tapped into creativity they didn’t know they possessed. We all – academics, learning-disabled researchers, family members and volunteers - learnt a lot about each other and the lived experience of learning disabilities today.

The participative research project had substantial public impact through public engagement activities including building a website and showcasing our work at the national Being Human Festival in November 2019. Attendees who completed the feedback questionnaire unanimously rated the experience as either Good or Excellent, because it helped them think about both learning disability history and research methods in new ways. Our event was featured in the organiser's Twitter Festival Highlights and blog. The project was also used by Jisc at DCDC19 - a conference co-hosted by The National Archives, Research Libraries UK and Jisc, and aimed at professionals and academics in the library, archive and heritage sectors - as an exemplar by for how archive material can be made relevant to new, unanticipated and under-represented audiences. So the project was not just about being inclusive for its own sake – it went a long way to meet the criteria for ‘good’ research by eliciting insider knowledge that would otherwise have remained untapped, having substantial public impact, and transforming the lives of the people involved.

* Funding: This work was funded by British Academy / JISC Digital Research in the Humanities Grant DRH18\180095

Owen Barden (bardeno@hope.ac.uk) is Associate Professor in Disability Studies at Liverpool Hope University. He is a core member of the Centre for Culture and Disability Studies, and Comments Editor for the Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies. He has contributed chapters to the Cultural History of Disability in the Modern Age (Mitchell & Snyder, 2020), as well as Disability, Avoidance in the Academy (Bolt & Penketh, 2016) and Changing Social Attitudes (Bolt, 2014), in addition to an extensive range of journal publications.

_____________________

Recommended citation:

Owen Barden (2021): Inside the History of Learning Disability. In: Public Disability History 6 (2021) 8.