By Jenny Schöldt

Translated by Ylva Söderfeldt

On May 3, 1868, a group of Deaf gathered together with a few hearing friends – today, we would probably call them ”allies” – at the Manilla Deaf-Mute Institute in Stockholm. The three initiators were the school’s hearing director Ossian Borg, the Deaf teacher Fritjof Carlbom from Tysta Skolan (“The Silent School”, another Stockholm Deaf school), and the artist Albert Berg. Carlbom had paid a visit to Berlin and, inspired by the Deaf club there, had decided to start something similar in Sweden. On this day, twenty-two Deaf and five hearing persons agreed to form the Deaf-Mute Society, Dövstumföreningen, predecessor of today’s Swedish Deaf Association. This remarkable event, a milestone in Swedish Deaf history, celebrates its 150th anniversary this month.

It was the actor Joakim Hagelin-Adeby, chairman of the Stockholm Deaf Society, who came up with the idea to stage a play in honor of the history of the Swedish Deaf movement and the banquets that were held in Paris in the 19th century to celebrate Sign Language. The title was going to be Parismiddagen – the Paris Banquet. His suggestion prompted Tyst Teater, a theatre company that has been performing in Sign Language for more than four decades, an audition for Deaf writers. The framework was in place, and now prospective playwrights were free to be creative.

When I found out about the idea, I immediately envisioned a table in a room, with two Deaf persons seated, signing: artfully, quickly, humorously, like I’ve seen my Deaf friends sit and sign so many times before, and like I’ve done myself. I often think of Sign Language as something that goes on in the room where it is ”spoken”, that can’t be translated or captured. Sign Language is a language without tenses, consisting, put simply, of lexical and non-lexical signs. The non-lexical signs are descriptive verbs that are modified (signs are not inflected) according to context, or created as a result of the syntax. Very much like what happens on a theatre stage.

To write a script in one language that is supposed to be performed in another one, because the latter lacks a written form, is a problem that has been discussed over and over again within Tyst Teater and the rest of the Deaf artistic community. In the past, for a different project, I had tried writing in a modified Swedish that made it clear how the lines were supposed to be signed. But this solution killed the creativity of the actors, and impeded the artistic work of the director.

I realized that I can’t decide how another Deaf person has to express themselves.

That has to happen in the room. In the conversation.

So this is why I wrote the play in Swedish. I was fortunate to know the previous work of the director, and to some extent the style and skills of the actors. The fact that they had to work with translation and interpretation gave the piece a dimension I now find invaluable.

Writing a play about a movement that is still ongoing, as a person who is part of that movement, is a strange and exhilirating meta-emotion, and perhaps something historians can relate to. A piece of history, alive, that I am observing and part of creating. Myself, and other Deaf. This was my intellectual starting point. I wanted to use my perspective on Deaf history, as it appears when I ask myself the question: what is Deaf history? Milestones such as the French signed education, the deaf schools, the official acknowledgement of Swedish Sign Language by the state in 1981, the Swedish Deaf movement. I want to be clear that I am concerned here with Nordic Deaf history, with a few links to other European Deaf communities and the US.

One table. Two signers. Leaping from one milestone to the other.

Then I started reading and exploring, somewhat, these milestones. I soon found myself annoyed at how most of the documented history of the Deaf dealt with the schools, or consisted of dull summaries of club proceedings and such. This gave me reason to reflect on why this is what the sources look like, questions that I incorporated in the piece. In this manner, I brought myself onstage, and I hoped that the audience would be able to identify with my experience, even if their questions weren’t exactly the same. Speaking of documentation, we are among the peoples that lack historical records, since we didn’t have written language, and since we are not born into our group. We are born into another linguistic community, and grow up among the hearing. In order to sign, we need other Deaf people. An somehow, we always seek out and find each other, and somehow Sign Language always finds us.

Words come and go, but the Deaf are here to stay.

Parismiddagen is currently on tour in Sweden. Some of the performances are accompanied by seminars on Deaf culture and history. See https://tystteater.riksteatern.se/parismiddagen/

Recommended Citation:

Jenny Schöldt: The Paris Banquet and the Swedish Deaf Movement, or: A Signed Room on Stage. In: Public Disability History 3 (2018) 7.

Translated by Ylva Söderfeldt

On May 3, 1868, a group of Deaf gathered together with a few hearing friends – today, we would probably call them ”allies” – at the Manilla Deaf-Mute Institute in Stockholm. The three initiators were the school’s hearing director Ossian Borg, the Deaf teacher Fritjof Carlbom from Tysta Skolan (“The Silent School”, another Stockholm Deaf school), and the artist Albert Berg. Carlbom had paid a visit to Berlin and, inspired by the Deaf club there, had decided to start something similar in Sweden. On this day, twenty-two Deaf and five hearing persons agreed to form the Deaf-Mute Society, Dövstumföreningen, predecessor of today’s Swedish Deaf Association. This remarkable event, a milestone in Swedish Deaf history, celebrates its 150th anniversary this month.

It was the actor Joakim Hagelin-Adeby, chairman of the Stockholm Deaf Society, who came up with the idea to stage a play in honor of the history of the Swedish Deaf movement and the banquets that were held in Paris in the 19th century to celebrate Sign Language. The title was going to be Parismiddagen – the Paris Banquet. His suggestion prompted Tyst Teater, a theatre company that has been performing in Sign Language for more than four decades, an audition for Deaf writers. The framework was in place, and now prospective playwrights were free to be creative.

When I found out about the idea, I immediately envisioned a table in a room, with two Deaf persons seated, signing: artfully, quickly, humorously, like I’ve seen my Deaf friends sit and sign so many times before, and like I’ve done myself. I often think of Sign Language as something that goes on in the room where it is ”spoken”, that can’t be translated or captured. Sign Language is a language without tenses, consisting, put simply, of lexical and non-lexical signs. The non-lexical signs are descriptive verbs that are modified (signs are not inflected) according to context, or created as a result of the syntax. Very much like what happens on a theatre stage.

To write a script in one language that is supposed to be performed in another one, because the latter lacks a written form, is a problem that has been discussed over and over again within Tyst Teater and the rest of the Deaf artistic community. In the past, for a different project, I had tried writing in a modified Swedish that made it clear how the lines were supposed to be signed. But this solution killed the creativity of the actors, and impeded the artistic work of the director.

I realized that I can’t decide how another Deaf person has to express themselves.

That has to happen in the room. In the conversation.

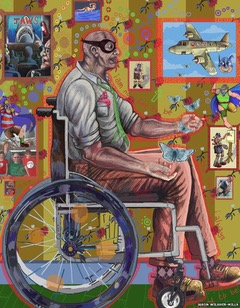

|

| Actors Joakim Hagelin Adeby and Mette Marqvardsen on stage, seated across from each other at a long table set for a banquet, dressed in historical costumes and signing. Photographer: Urban Jörén |

So this is why I wrote the play in Swedish. I was fortunate to know the previous work of the director, and to some extent the style and skills of the actors. The fact that they had to work with translation and interpretation gave the piece a dimension I now find invaluable.

One table. Two signers. Leaping from one milestone to the other.

|

| Actors Mette Marqvardsen and Joakim Hagelin Adeby on stage, Marqvardsen with a pipe, Hagelin Adeby with glasses, shaking hands and cheering. Photographer: Urban Jörén |

Then I started reading and exploring, somewhat, these milestones. I soon found myself annoyed at how most of the documented history of the Deaf dealt with the schools, or consisted of dull summaries of club proceedings and such. This gave me reason to reflect on why this is what the sources look like, questions that I incorporated in the piece. In this manner, I brought myself onstage, and I hoped that the audience would be able to identify with my experience, even if their questions weren’t exactly the same. Speaking of documentation, we are among the peoples that lack historical records, since we didn’t have written language, and since we are not born into our group. We are born into another linguistic community, and grow up among the hearing. In order to sign, we need other Deaf people. An somehow, we always seek out and find each other, and somehow Sign Language always finds us.

|

| Actors Joakim Hagelin Adeby and Mette Marqvardsen on stage, standing behind the table holding up a banner that reads, in Swedish: "TO BE. DEAF. SIGN LANGUAGE FOR ALL." Photographer: Urban Jörén |

Words come and go, but the Deaf are here to stay.

Parismiddagen is currently on tour in Sweden. Some of the performances are accompanied by seminars on Deaf culture and history. See https://tystteater.riksteatern.se/parismiddagen/

Recommended Citation: