By Giorgia Vocino

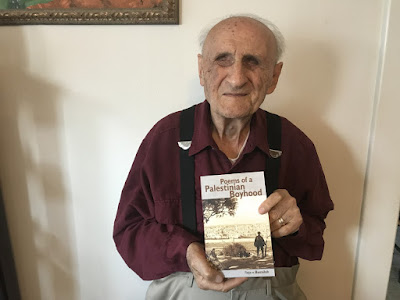

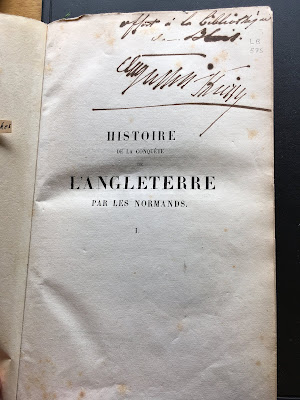

Born in 1795, shortly after the end of the reign of Terror, Jacques Nicolas Augustin Thierry was an enfant prodige. Born in a modest family, delicate and often sick, he could not live off his family income nor start a military career, but he could count on his sharp intelligence to climb the social ladder. Graduate from the École Normale, in 1811 he started working as the secretary of Claude-Henri de Rouvroy, count of Saint-Simon. Vibrant supporter of the liberal party and close to the milieu of the Carbonari, Thierry began an independent career as a journalist, but was soon drawn to the study of history: in 1820 he published in the Courrier Français nine Lettres sur l’Histoire de France, while in 1825 the publication of the Histoire de la conquête de l’Angleterre par les Normands crowned him as a historian and won him a place among the most reputed scholars and authors of his time. It was in those years of hectic and passionate study that his health problems started to take a toll on his life and his work.

|

| Signed copy of l'Histoire de la conquête (Bibliothèque Abbé Grégoire) |

Thierry’s eyesight progressively declined and eventually left him blind. Thought to be the consequence of a work rhythm that was too demanding, he was dubbed the Homère de l’histoire by Chauteaubriand. The legend of a young and heroic martyr for science started to take shape. Blind and progressively afflicted with paralysis, the historian showed the symptoms of an undiagnosed syphilis that made it impossible for him to work without the assistance of others. Despite his condition, Augustin Thierry maintained a remarkably intense work routine that allowed him to publish new works and to restlessly revise his oeuvre.

|

| Corrected Proofs of the Récits des Temps Mérovingiens (Blois, AD41_F_1946B) |

For the following thirty years, Augustin Thierry was assisted by secretaries and other collaborators whose names remain in the shadows. The archives of the Thierry family still preserved at Blois are a precious testimony to the functioning of the group of people surrounding the historian and working with him and for him. Thirty notebooks, known as the Cahiers de la chambre, were filled in between 1836 and 1844 with drafts, excerpts of sources, reading notes and personal memos that give shape to Augustin Thierry’s intellectual and social small world. Available for consultation on the website (shelf-marks Blois, Archives départamentales des Loir-et-Cher, F 1576 and F 1577), these notebooks constitute one of the most interesting, yet enigmatic documents in the Thierry archives digitised by the ArchAT project (Université d’Orléans – IRHT CNRS, project blog). Many hands can be spotted in their pages alongside one another, hands whose identification is a challenging operation that has never been attempted.

|

| The Cahiers de la Chambre (Blois, AD41 F 1576 and 1577) |

Among these hands one can find Augustin’s official collaborators: his personal secretary Charles Cassou as well as Martial Delpit, a graduate from the Ecole des Chartes salaried by the government within the frame of the national project of the Monuments du Tiers Etat supervised by Thierry. Scholars themselves, both men assisted Thierry in the study of the sources that laid the foundations of his history writing, chiefly the Récits des Temps Mérovingiens, and helped him with the revision of his earlier works and the drafting of new publications. The impossibility to lead his research autonomously casted a shadow on the originality of Thierry’s works already in his lifetime, as it is proved by an article published in 1837 in the Revue des Deux Mondes in which Désiré Nisard openly acknowledged the role of collaborateur for Augustin’s secretary Armand Carrel (deadly injured in a duel in 1836), while Thierry claimed full and exclusive responsibility for his literary output.

|

| Draft letter to the director of La Revue des Deux Mondes (Blois, AD41, F 1576 02) |

As a matter of fact, the blind historian could count on many sets of eyes, first of all those of his wife, Julie Thierry, herself a literate woman and a novelist whom he married in 1831. Julie’s pivotal role in Augustin’s everyday life can hardly be underestimated, but her work as an assistant emerge clearly from the notebooks where her hand drafted letters and noted down the words dictated by her husband. Furthermore, less literate scribes can also be found in the Cahiers de la chambre: their faulty orthography and unpolished handwriting make clear that they were not salaried secretaries, but off-the-record assistants most likely chosen among the household help. Augustin’s footman was probably responsible for writing down Augustin’s thoughts and work instructions, and years later, in the 1850s, it was his personal physician Gabriel Graugnard who not only took care of the by-then completely paralysed historian, but also helped him in his scholarly work.

|

| Handwriting of Augustin Thierry's Footman (Blois, AD41, F 1577 8) |

The study of Augustin Thierry’s archives and particularly his notebooks thus allows us to get glimpses of the creative process behind the writing of an author who could not write. In particular, the analysis of the complex documents that are the Cahiers de la Chambre opens for us a window on the everyday work routine of a blind historian. The centrality of the spoken word and the practical, and yet crucial organisation of the writing thus come to the fore as key research areas. The nineteenth-century Homère de l’histoire was surrounded not only by his official secretaries, but also by informal and too often forgotten assistants whose existence and importance should not be overlooked. The ArchAT project therefore has the ambition to describe the wider scholarly network as well as the small domestic world in which Augustin Thierry conceived and worked on his oeuvre and more specifically on his masterpiece, the Récits des Temps Mérovingiens. This means reconsidering the boundaries of authoriality and highlighting the choral dimension of the writing of his best seller, the influence of which can still be observed on the ideas about the Early Middle Ages, understood as a dark and violent time, that are deeply rooted in the collective imaginary.

Giorgia Vocino is a post-doc in the ArchAT projet (University of Orléans – IRHT-CNRS).

_____________________________

Recommended citation

Giorgia Vocino (2019): Augustin Thierry and the Many Eyes of a Blind Historian. In: Public Disability History 4 (2019) 11.