Parents on the March: Disability, Education and Parent-Activists

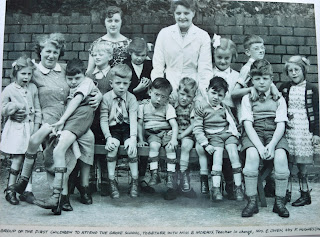

By Teresa Hillier , Swansea University At a time of great social change in mid-20th century Britain there was a series of parliamentary reforms which aimed to help rebuild a war-torn society. These included a focus on education with the 1944 Education Act aiming to provide equality of opportunity to children. However, many children with cerebral palsy and related disabilities were classed as ineducable under this Act. This led to parents campaigning on behalf of their children against this perceived injustice. These parents were pioneers and disability activists, drawing public attention to the exclusion from education of their children. As a result of this direct action many parent-led organisations were established during the 1950s one of which is Longfields Association originally known as Swansea and District Spastic Association . Legacy of Longfields is a two-year research project that will examine and share the history of the Association. The organisation was set up in 1952