People of short stature as representatives of the gods?

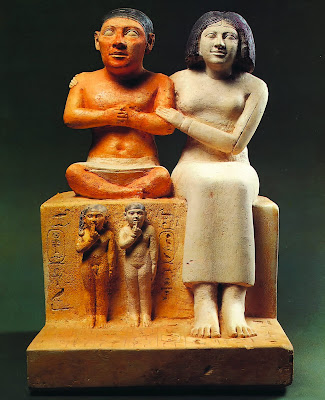

By Bert Gevaert, PhD Seneb and his wife Senetites (ca. 2520 BC) (Egyptian Museum, Cairo) People of (unusually) short stature 1 are extremely popular in art: portrayal of people with so called ‘proportionate’ or ‘disproportionate’ short stature (usually achondroplasia) can be found all over the world and through the entire history of mankind. People of short stature were popular in ancient Roman and Greek art, but also in Asian, African and Latin American cultures. Fascinated by the tiny appearance of their fellow human beings, artists from Classical Antiquity till today liked to sculpt, cast, draw, paint, photograph or film people of short stature. Do these persons remind them (and us!) of ancient mythology about people of short stature living in faraway places? Do they attract us by their doll-like features? Are they funny, simply because they are smaller than ‘normal’ people? Some people consider them as more than funny, in their opinion they are ridiculous and for them they